‘The Little Dragon’ Bruce Lee’s Influence on Martial Arts Films

‘The Little Dragon’ Bruce Lee’s Influence on Martial Arts Films

Bruce Lee is often heralded as the greatest martial arts star to grace the big screen. Though that might come across as a statement of hyperbole, I think that one cannot deny the impact that his martial arts films and philosophy have made. Martial arts stars including Jackie Chan and Donnie Yen have cited him as an inspiration for their own films. Despite Bruce’s short lived martial arts film career, he challenged the established conventions and paved the way for future film makers and actors.

The martial arts films in the 1960s were mostly directed by King Hu (Come Drink With Me, Dragon Inn) and Chang Cheh (One-Armed Swordsman, Golden Swallow). While they had a big influence on the genre, their styles were rooted in the operatic traditions. Their films were mainly period wuxia pieces that drew more on narrative and heroic characters to establish the film. Fight scenes often employed quick cuts or editing tricks to give the semblance of action.

Stills from Dragon Inn (1967) and Come Drink With Me (1966), dir. King Hu

What set Bruce apart was his attitude toward the various kungfu styles that existed in different schools. He viewed the classic doctrines in traditional styles as being held in rigidity and sought to change it by essentially having none. Bruce’s own philosophy, Jeet Kune Do, rejected the dogma of the classical styles, opting instead for more free flowing combat that was adaptive. In Black Belt magazine, Bruce describes it as “the direct expression of one’s feelings with the minimum of movements and energy.”

Bruce’s film career can be traced back to his childhood days, but it wasn’t until his adult years that he began to showcase his martial arts skills on both television and film. After being under Ip Man’s tutelage, his experiences in America would continue to shape his philosophy of martial arts. His roles in America, including playing Kato in The Green Hornet introduced him to American audiences, but the cultural frictions that existed did not allow Bruce to fully express himself.

After returning to Hong Kong in 1971, Bruce landed his first leading role in The Big Boss, directed by Lo Wei. His Jeet Kune Do practice brought on to the set a simplicity among many stuntmen who were trained in the opera. There was less of the theatrics used in wuxia films like wire-fu and spurting fake blood in favour of a more direct form of combat.

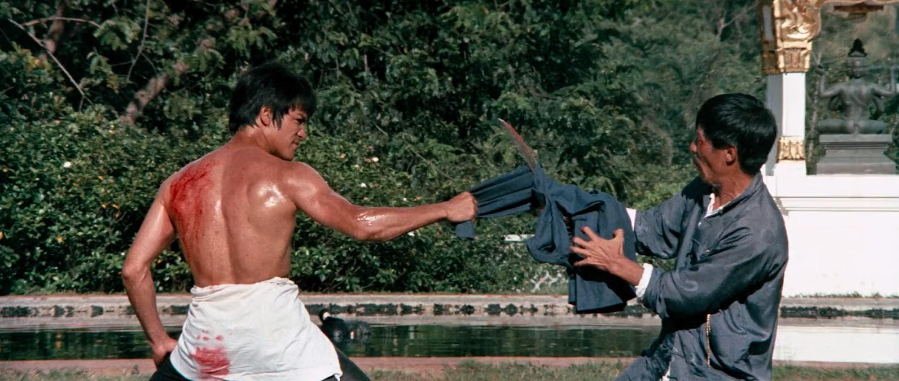

Still from The Big Boss (1971), dir. Lo Wei

It was this ethos that conveyed a minimalist approach to his on screen fights, which proved to be radically different than his comtemporaries. Instead of using a plethora of weapons, Bruce mainly used his feet. His speed also largely contrasted the slower pace of combat normally seen in 1960s martial art films. To capture the hits, shots were held for longer periods with less cuts or close ups.

Still from The Big Boss (1971), dir. Lo Wei

However, The Big Boss still carried the influences of the late 60s, occasionally using wires or low camera angles to create the effect of leaping up high. In scenes where Bruce was up against a group, the scene still felt staged to a certain extent. However, The Big Boss initiated the transition of martial arts films that carried more realistic combat.

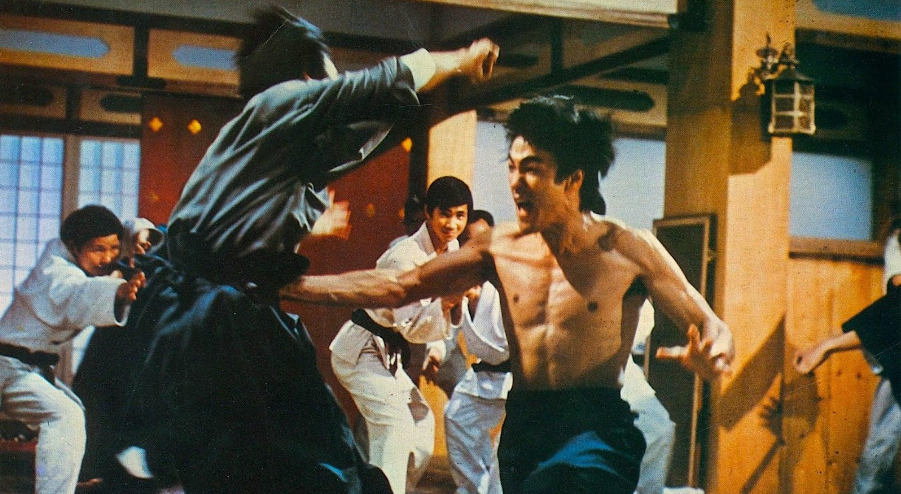

After the success of The Big Boss, Bruce starred in Fist of Fury in 1972. In it he played Chen Zhen, a fictional student of folk hero Huo Yuanjia. After his master’s death, Chen Zhen returns to Shanghai and finds himself battling the influence of Japanese colonialism. Bruce took on the role of action choreographer, and so his philosophy of Jeet Kune Do becomes more salient in this film. More wide shots are used to display the movement of his body, even if there’s less flair to each hit. Bruce sought to capture the full breadth of the attack, from the movement, to the impact and reaction. The framing also helped to highlight Bruce’s speed and agility, capturing his kinetic display of movement.

Still from Fist of Fury (1972), dir. Lo Wei

Like The Big Boss, longer shots heightened the believability of combat as audiences saw the fight unfold in real time along with the reaction. It did however require more actors who had experience in martial arts or stunts. In Fist of Fury, Bruce’s student, Robert Baker, was cast as the final antagonist. It allowed for a more intense fight sequence between two experienced martial artists. Similarly in The Way of the Dragon, Chuck Norris made his film debut as a black belt with a 10 minute fight scene in the Coliseum.

Still from The Fist of Fury (1972), dir. Lo Wei

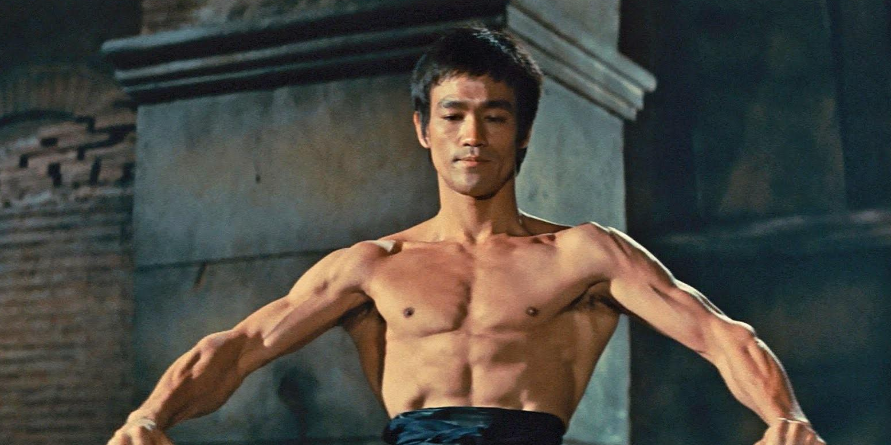

Still from The Way of the Dragon (1972), dir. Bruce Lee

The casting of practitioners in martial arts films seems to have begun during this period, and carried on even after Bruce’s death. Even though the types of films shifted back to period pieces, the late 1970s saw new levels of action complexity by action choreographers turned directors such as Lau Kar-leung (The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, Heroes of the East). These films, while returning to their opera inspired roots featured martial artists such as Gordon Liu and Lo Lieh who were able to execute what was demanded of them.

Apart from his fight philosophy, Bruce’s physique on screen also reshaped how strength was viewed in martial arts films. Shaw Brothers actors like Jimmy Wang-yu and Ti Lung, despite their physique, did not display much of it in their films. In scenes where Bruce takes off his shirt to reveal his body, it functions as a visual to indicate that the action will escalate. Bruce’s character is also not portrayed as invincible. His persistence in fighting through the pain, with the “blood stains” on his torso exemplify the kind of strength that he wanted to portray. The characterisation of the male lead in martial arts films went from simply being a chivalrous hero to one that embodied the notion of masculinity, an influence that Bruce likely borrowed from his experiences in America.

Still from The Way of the Dragon (1972), dir. Bruce Lee

This expression of strength and masculinity was adopted early on after Bruce’s death by stars like Alexander Fu Sheng in Five Shaolin Masters and later on by Jackie Chan in Fearless Hyena. It served to not only denote the protagonist of the film but also to signify a certain level of vigor they possessed.

The changes in the way martial arts films were directed and perceived in the years preceding and following Lee’s work show that his ideas made a significant impact. Although the years following his death saw a shift back to heavily choreographed films, it made a return to more realistic combat in the late 1970s after Lo Wei sought to model the then young Jackie Chan to take after Bruce Lee in New Fist of Fury.

It is likely that Bruce’s Jeet Kune Do philosophy felt esoteric, such that few directors, action choreographers, and actors were able to adopt it. However, the disruption that he brought to martial arts cinema stirred up a generation of film talent to create more complex fight choreography that would impress audiences who wanted to see the action unfold. It would lead to the popularity of Jackie Chan who created his own brand of action comedy, and in more recent years, Donnie Yen, who incorporated mixed martial arts into his films. Even after death, his Jeet Kune Do philosophy has been imprinted into the fabric of martial arts films.

——————————————————————————-

This review is published as an extension of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme organised by The Filmic Eye, with support from the Singapore Film Society.

About the Author: Ivan Chin has a penchant for Hong Kong cinema and science-fiction films, but enjoys anything from blockbusters to the avant-garde. His favourite directors include Johnnie To, Denis Villeneuve and Stanley Kubrick. He also fervently hopes to see local films blossom. In his free time, he can usually be found wandering around cinemas.

——————————————————————————-