Emulsions Between Women and the Sea

Emulsions Between Women and the Sea

There has been a striking, if contentious¹, use of water in association with women. Though all bodies gestate in water, each comprising 60-90% of water, the essentialist take on water to signify women is derived from the amniotic fluid of the female womb. Mythology personifies the dangers of the sea by evoking the wrath of sisters and distinctly feminine song. Rather than alerting us to some ‘essentialist’ difference between masculine and feminine” Astrida Neimanis proposes in Bodies of Water that women's writings on bodily, watery fluids “invite[s] all bodies to attend to the water that facilitates their existence, and embeds them within ongoing overlapping cycles of aqueous fecundity.”² In identifying conflicting extremities of bodies of water coded in the feminine as protective, nourishing, restorative and destructive, this article is interested in what is withheld, of what cannot be encapsulated, of a privacy that refuses portrayal, just as the depths of oceanic bodies cannot be discerned.

Buoyed by waves in their notation of periods in their history, there seems to me a resonance between cinema and feminism, one that seems ripe for examination. This article, therefore, presents loose studies of water bodies rendered on screens wide and 13 inches in length, viewed in Singapore in 2022. Though several films were observed to have rendered water, particularly beaches, on screen, the films in focus here are Park Chan-wook’s Decision to Leave (2022)³, Marie Kreutzer’s Corsage (2022)⁴ and Kaori Oda’s Cenote (2019)⁵ for their evocative depictions of women and their rendered images in relation to the sea.

It might have begun in Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013) when amidst its controversies or in spite of it, Adele continues dancing to Lykke Li’s “I Follow Rivers” and later swims out to floats in the sea, far from all she has wronged for the brief lightness of a broken heart. But the radical turning point that is Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) sees Marianne jump without hesitation to retrieve the canvas she needs to earn her keep and delivers her sea-soaked on an island in Brittany where an altering love awaits. Likewise, Decision to Leave, Corsage and Cenote mark a return to water, situating the oasis of women in the impossible sea. Here, the infinite stretch of water and ecotones is portrayed as an inviolable and sanctified distance between the subject of the camera, the leading women and their entourage to facilitate their being able to finally exhale, and consequently respire, away from the suffocating constraints of presentation.

Decision to Leave

Hae-jun (海 — sea, 俊 — a handsomeness associated with royalty) may have served in the Korean navy, but Song Seo-rae (宋瑞莱 — just a name my mother says) emerges rebirthed at sea. Hae-jun’s wife says as much, when he breaks into a jingle about being a man of the sea, ripping his padded jacket to reveal his bare chest and boxers, “Man of the sea, my ass. You were born in downtown Seoul.” By contrast, Seo-rae “spent ten days at sea in the heat of summer in a fish storage bin. My face was like a skull smeared with faeces. I was rocking back and forth like a mad person” in her escape from China to South Korea. He is the sea only in name really, and is most alive when chasing murderers on steep inclines.

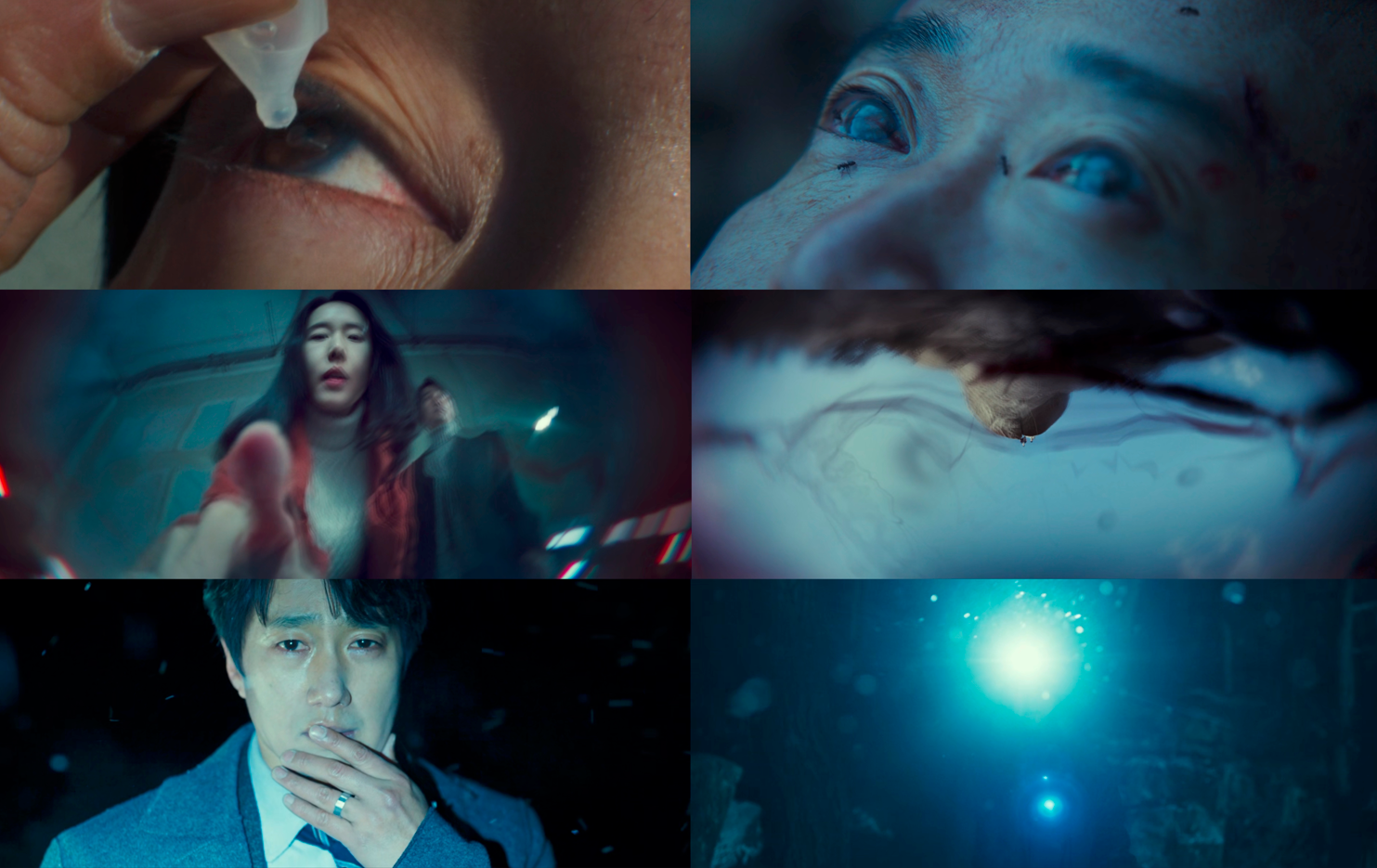

He certainly thinks himself a lover of the sea—“Me too,” he answers and hides his smile when Seo-rae cites Confucius, “I am not benevolent. I like the sea.”—and he is. So too, her besotted husbands who scale some pillar of love and plunge to their deaths. The first, an avid mountaineer, from being pushed off a mountain; the second having been stabbed and pushed into a pool. If anything, Hae-jun loves especially the clarity of a case revealing its truth, the kind of panoramic view one gets at the summit of the mountain, when the horizon of the sea can be seen. He moisturises his eyes through the film to see clearly but his vision gets increasingly foggier than before, lights rendered sharp and glaring. Frustratingly, the liquid solution he drops into his eyes to clarify his vision serves only to obscure it. They get as blurry as the eyes of dead husbands and fish. While he puzzles over the case—over Seo-rae— regarding her central, open face, noting her every move, he does not see that what he really should be studying are effigies of the sea endlessly patterned over the walls of her house and notebook. He misses the point that she perhaps doesn’t want to be seen—at least the parts that might push him away—only to be desired for whatever drew him to her in the first place, “Treat me as you will, like you always did, as a suspect.” The kind of thrill that comes with figuring out the person, right before the answers are derived.

Questioned about her reappearance in Ipo, Seo-rae replies that she “like[s] the mist”. She means Jung Hoon-hee’s ‘Fog’, the song that pervades the film, the blessed fog that rises from the surface of water to accompany and embrace the solitary figure in the song. Above all, she means the dense impossibility of the relationship between herself and Hae-jun. She seeks the sea in him, an overwhelming, larger than yourself kind of love. But when he rejects her after she reveals herself to him, she digs a hole in the sand and disappears into the deep, leaving a small mountain of sand behind where the sea might erode it to bury her without a trace. From water, Seo-rae returns to water. May Hae-jun haunt her past the point of death, to look at the sea and see only her. The last thing we hear of her is the sound of her breathing, her first solitary breath in a while. This time, her breath is all her own, nothing of its initial introduction to lull Hae-jun to sleep. She “go[es] into the sea… go[es] deep… a jellyfish… no thoughts. No joy and no sadness… no emotions” to literally erode the mountain on which Hae-jun scales in his investigation into her, as if she never existed. A clean slate.

Corsage

Submerged in a copper bathtub, Empress Elisabeth of Austria keeps her eyes wide open. When she surfaces, she doesn’t gasp for breath but asks instead, “How long?” A minute and eleven seconds. Disappointed by life at large, the film sees her through continuous retreat into the bath, finding consolation and rest in its shallow depths. If being laced in increasingly tight corsets to maintain her figure—in which one of her handmaidens, in Empress drag, is so suffocated that she vomits—seemed at first a vanity project to hold fast to lost youth, the breathless years Elisabeth spends in her corsets become consolidated practices for when she finally makes the decision to leave for expansive seas, her time underwater the only time she gets to breathe, as it were. The bathtub isn’t so much a withdrawal from the world as it is a vessel in which preparation for her disappearing act can be enacted.

The Empress is identified and recognised both for and by her impossibly slim waist and veil masks she puts on at public events. For all the iconicism of her appearance, however, she easily transposes these images onto her handmaidens in the third act. The illusion is so successful that her daughter mistakes the silhouette of the handmaiden for her mother and is in thrall of that particular moment, “You were very dignified that day.” There’s it then: that necessary trigger to single-mindedly go ahead with the plan, the knowledge that her daughter doesn’t quite need her but the image of an Empress plans to leave a trail of handmaidens who can take her position in her wake and plunges out of the frame into the sea. The image cuts right before the moment of euphoric release as she hits the water so it belongs only to her.

Cenote

If Decision to Leave and Corsage see a disappearance to the sea, Cenote takes place within water bodies themselves, offering a means to immerse and live with-in water. The film sets out by historicising cenotes as an ancient site of ritual sacrifice for the Aztecs and its complex network of canals that link to other cenotes. Its dense network does not discriminate between local and professional divers (who must be certified for cave dining and special equipment to navigate the drastic changes in light and saline levels in the water), all of whom are susceptible to disappearing in its currents, sometimes resurfacing in cenotes nearby or not at all. The camera sweeps in and out of brilliant light to cave darkness, with slight changes to camera angles lending the film qualities of a horror film: how deep exactly, are those dark canals?

As opposed to the terror that accompanies horror, the film drifts across the crevices of cenotes and portals to canals, a light gliding by in some instances of complete darkness. The navigation inherent to discovery is not present. Instead, Oda allows both herself and the camera she wields to move with the currents:

While [the fish] swam in circular movements, I followed them. It wasn’t clear to me

while I was filming but when I saw the footage, I realised that my body with the camera

was often synchronised with them. They felt like moments when I no longer was an

alien object in the space. Nor was the camera. I realised in my edits, that I was gathering

footage where I could sense this synchronicity from the image; the inability to

differentiate between worlds.⁶

To allow oneself to be completely taken up by the currents would be tantamount to death. However, Oda’s “synchronicity”—that moment of recognition and instinct to move with or against the flow and remain suspended in some central space—that requires a balancing act between having enough knowledge and respect for and of forces beyond the control of any singular entity. Thus, Oda casts herself as a quiet companion to the viewer with whom she invites along to look at the darkness, all the while following the light whenever it appears. To rest easy with terror of the unknown.

About the Author: Sasha seeks to reify the fugitive effects of looking through language. She received her BA in 2021 and has worked with HBO Asia, the Singapore International Film Festival and the National Archives of Singapore.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

¹Stefan Helmreich, “The Genders of Waves,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 45, no. 1 & 2 (2017): 41-43.

²Astrida Neimanis, “Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water,” in Bodies of Water (Bloomsbury, 2017), 89. Neimanis examines the works of, amongst others, Virginia Woolf, Luce Irigaray, Hélène Cixous and Trịnh Thị Minh Hà.

³Screened at various cinema chains across the country.

⁴Set to premiere in January 2023 in Singapore.

⁵Screened as part of the Radical Whispers: Asian Documentaries and Shorts programme at the Asian Film Archive.

⁶Kaori Oda, “Toward a Common Tenderness: An Interview with Kaori Oda,” interview by Aiko Masubuchi. Mubi Notebook, March 17, 2020,

https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/toward-a-common-tenderness-an interview-with-kaori-oda.