Film Review #125: BRATAN

BRATAN Review

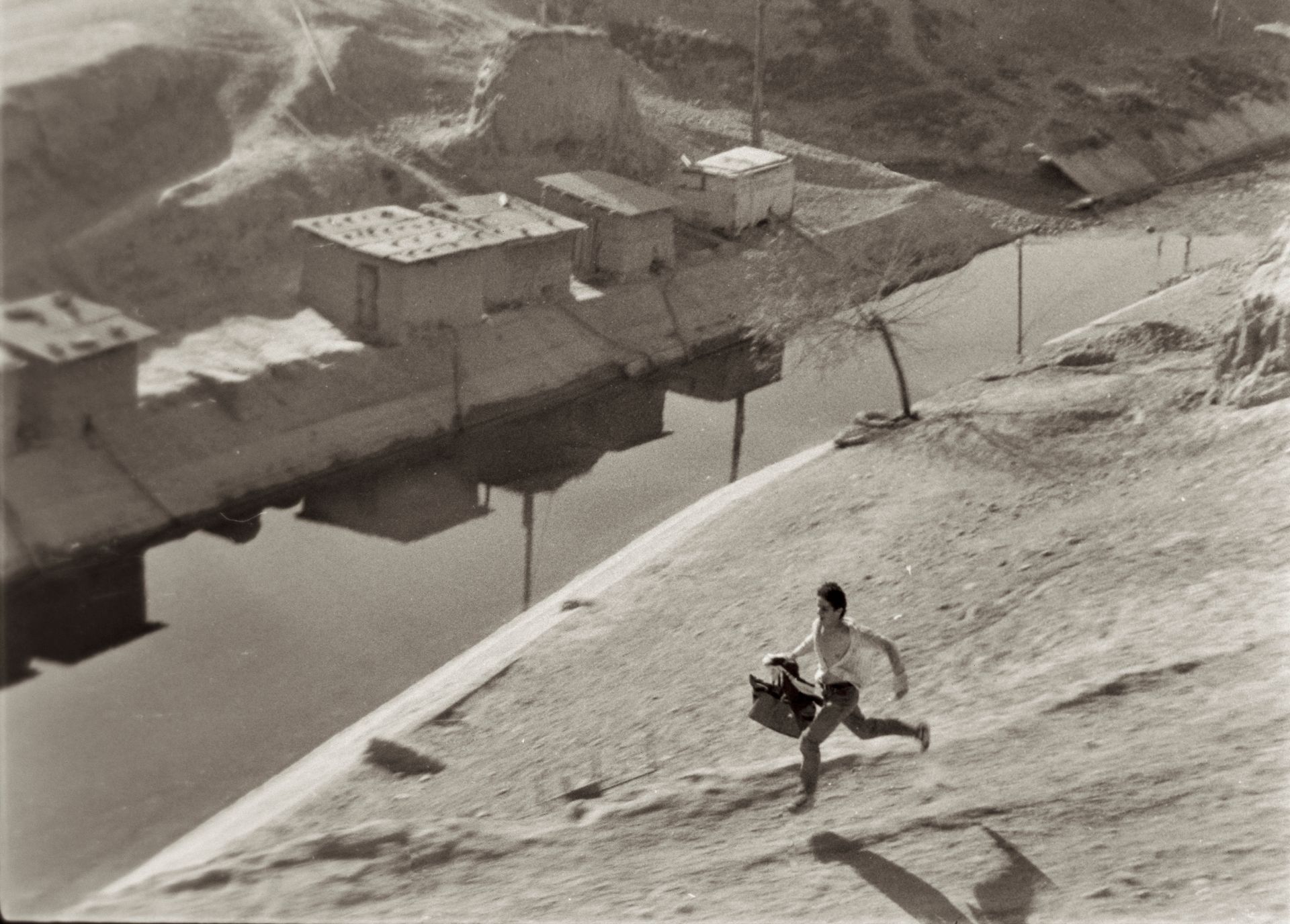

Tajikistan — it’s not everyday you get a chance to catch a film from this lesser-known region in central Asia, surrounded by Afghanistan, China, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Hailing from the 90s, director Bakhtyar Khudojnazarov made this debut film at 25. However, it premiered only a couple of years back posthumously, thanks to his friend and colleague, German filmmaker Veit Helmer, who discovered it and went through the painstaking and pricey process of restoration.

Thankfully he did, so we get this gem.

Bratan, or

Brother, tells the story of 17-year-old Farukh (Firus Sasaliyev) and his younger brother, nicknamed Pontsjik, or Pancake (Timur Tursunov), who stay with their grandmother. Living in poverty, Farukh engages in petty theft to make ends meet. The brothers embark on a freight train ride across the deserted countryside to visit their long-lost father, now a successful doctor, in hopes of a better life.

A certain importance underscores this film as it was made during the Perestroika-era, and right before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In dreamlike black and white, the film captures parts of Tajikistan beautifully, despite the industrial, barren and dusty environment; watching this film feels like stumbling on a relic of a forgone past.

Post-independent Tajik film pioneer Khudojnazarov studied at the prestigious Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. He went on to make

Kosh ba Kosh

(1994), which won the Silver Lion at the 50th Venice International Film Festival, and

Luna Papa (1999).

In this film of familial responsibility, how the brothers were treated can be seen as a mirror for Tajikistan’s circumstance when it declared its independence in August 1991. Just like how they’re left to their own devices and have to fend for themselves despite their father’s affluence, Tajikistan had to stand on its own when the Soviet Union collapsed.

They get by.

Bratan is a beautifully crafted story peppered with humorous moments. The two brothers were well-casted, with such natural chemistry to bring out their unique relationship of sibling-guardian. Pancake is extremely adorable with his little stubby tummy, often getting bullied or picked on. But he also has a weird penchant for eating something

very inedible (we’ve probably heard stories of children eating inconsumable objects much to the chagrin of parents, but Pancake takes it up a notch, amusingly). His crying can be quite hammy at times and there were a couple of abrupt cuts but these can be shrugged off.

Hardy older brother Farukh is a natural on-screen, charismatic chap. He’s a maturing teenager but has to step up as his brother’s guardian, being in shoes that are too big for him. This results in jocular twists when the duo encounter various situations, reminiscent of tough love, but stopping short of the full-blown parental nurturing and care.

I found it quite ambitious for Khudojnazarov’s debut film to be a rail film and to feature children and animals — not an easy feat, considering the risks and unpredictability involved. It paid off. When the credits rolled, I was surprised that time had passed so quickly.

Hop on if you ever get the chance to watch this charming, heartfelt journey. Watch the trailer

here.

About the Author: Kennice reads, writes, dances, and watches theatre and film as a way to understand life on Earth (& perhaps beyond). Probably thinking of having another cup of yuan yang siew dai.

——————————————————————————-

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.