Your Name Engraved Herein;

Your Name Engraved Herein;

Your Name Engraved Herein is one of the highest grossing, and consequently one of the most significant films, for pride representation in Taiwan. With its reviews setting the bar high, we would expect its angle on queer relationships to be groundbreaking and deeply emotional, and it no doubt delivers.

As is a common trope for queer love stories, there are multiple factors that hold the characters back from being together. The movie is set in a time where Taiwan is freshly recovering from a politically tenuous period of military rule. To add on to that tension, the characters find themselves in a religious school.

How does the film make sense of forbidden love?

Arguably, the strongest external factors preventing the couple from being together are religion and the remnants of military rule. Though you’d automatically think both are anti-queer, the film surprisingly pits one against the other. In the above scene, a commander-like school attendant demands greater gender segregation of the students, only to be met with the voice of reason from the priest of the school. This repeats itself throughout the film - the military-esque characters retaliate against the queer community, while the priest empathises with our protagonists.

This conflict progresses as follows: the tight militaristic imposition, both in school and at home, are external pulls of the conflict, while the protagonists' frustrations are processed internally through religion. The two factors work together to tell the story dynamically, without clumsy shortfalls.

Religious Redemption?

When it comes to conversations on queerness, religion is often the elephant in the room. We’re naturally compelled to watch how religion and queerness interact and how the characters reconcile the conflict. A part of why we love such stories could be because we’re constantly hoping to see a positive reconciliation without giving up either of the two. Nonetheless, this cognitive dissonance is very real, making the movie all the more relatable.

In our post-film chat, we spent some time discussing this trope and our personal opinions about it - as should happen in any safe platform to discuss pride and LGBTQ issues. Here are a couple of conclusions we landed on:

1. Movies that portray the conflict allow audiences to empathise with the struggles of LGBTQ folks. It also eases the hearts of queer individuals, to see aspects of themselves represented in mainstream media.

2. Where most of the world is still against same-sex marriage, the film trope of religion against sexuality also helps to provide a platform for religion to portray itself in a more empathetic, and less aggressive way, than in real life.

Stereotypes, aggression and lack of understanding prevent us from loving each other as fellow humans. Any media that starts conversations is important, and in igniting our conversations, Your Name Engraved Herein continues to be an important piece of work.

But outside of this ‘religion vs. sexuality’ conflict, does this film stand on its own?

Character development in dealing with the conflict

How was this conflict presented in the film? There is a melodramatic mechanic that was used throughout - the characters yell at and beat each other, a lot. That physical aggression that seems normal of teenage boys makes our protagonist, A-Han’s, primal scream at the climax a flimsy payoff because it is the hundredth time we see him being violently impulsive. Perhaps if there was more restraint, the characters would have been more multi-dimensional? It would also have nicely contrasted A-Han’s internal conflict (religion) with the need to maintain secrecy due to external restrictions (military-esque law and family). The scenes of his breaking out/down would then have had a stronger impact, highlighting the break in his character and faith, strategically bookmarking his character arc as well.

Let’s dive deeper into what ‘queer love’ is and why we continue to look out for good queer films.

What does Queer Love in film aim to achieve?

A key topic in the post-film discussion was the representation of queer love. Since Liu (the director) had hoped for the movie to celebrate queerness and inspire queer communities in Asia, some audiences expected positive queer representation, but were disappointed in its potentially problematic scenes of non-consensual sex. (We also noted this as a common trope in other queer coming-of-age films.) But if Liu’s goal was to show “homosexual love is the same as heterosexual love”, it seems unjust to match this movie to the modern gold standard of what good queer representation ought to be.

We discussed how the shower scene represents a key point in the film despite its invasiveness. Pleasure, pain and shame mix with water and tears as the “couple” is forced to confront their desire amidst self-repression and betrayal. In its blatant violation and animalistic lust, we are rightfully disgusted (by the non-consensual nature) and made to feel sorry for a relationship so fractured from the casual flirtatious banter that opened the movie.

The shower scene echoes a previous scene where A-Han leans in attempting to give Birdy a kiss while he’s asleep. A recognisably romantic atmosphere is present in the soft red lights, plush velvet couches and close, intimate angles. However, the lack of consent is jarring and the attempted kiss is interrupted. This is a central problem in the film: a crippling inability to communicate romantic attraction in a healthy way, all the while monitored by a society hostile to their existence.

This is the homosexual struggle in 1980’s Taiwan. When love is infringed upon by societal prejudice, self-repression and religion, one can say that the external and internal never disentangle, the personal is the political. They are victims of their time, and this hurt translates into violent and destructive ways. A-han’s non-consensual breech on Birdy and Birdy’s intentional pursuit of Ban-Ban (the female friend) to hurt A-han both stem from a deep self-repression, the inability to understand how homosexual love can exist.

In this way, the gold standard isn’t met, but for very clear alternative messages.

Does this really fall under the ‘Romance’ genre?

A central question for a typecast romance film was: why did so many find it unromantic? Some decried the actors as lacking chemistry, while others found it lacking in comparison to other Taiwanese romance films. For what seems to be a romance, its plot is driven by frustration rather than love. The characters do not pursue love in the personal, insular sense. Instead, their principal struggle is to comprehend if their love can exist in their time.

We see A-han frustrated, defending his love as pure and special to Father Oliver, yet making an unwelcome move on Birdy and having wet dreams. A-han’s desire to elevate his love by separating it from lust is futile. He subjects himself to a restrictive model of love, one that cannot harbour variation without collapsing on itself. This internal conflict is highlighted again in his conversation with his mother. She asserts that procreation “turns to love over time”, something he rejects. This is the crux of his frustration. By basing his idea of love on a heterosexual model, any concept of homosexual love is defined against a standard that is inherently discriminated.

We see them grow into this realisation at the end. Wiser and older, they reflect on the ways in which they and Father Oliver attempted to discourage their homosexuality. The movie does not end on any explicit display of affection. Instead, past and present meld as the camera smoothly angles away from their old selves to their youthful past, now displaced and presented frolicking amidst Canadian (foreign, not home) streets. This juxtaposition is bittersweet, their love was always out of sync with their times.

On Taiwan’s legalisation of same-sex marriage, Liu states that “When I saw people celebrating on the streets, I actually felt a little bit sorrowful because for the people from my generation—who were born in the ‘70s, for example—it may be too late for them”. Birdy and A-han were too early.

How do the actors contribute to our understanding of the film and its goals?

During our post-film discussion, some of the viewers mentioned an interesting comment about the actors’ looks. Edward Chen and Tsing Jin-Hua, who played A-Han and Birdy respectively, are just too … stereotypically good-looking for teenage boys with raging hormones. While a seemingly shallow critique at first glance, it is a much-needed insight into how desirability plays into our acceptance of LGBTQ+ films. Good-looking actors are not exclusive to LGBTQ+ films and of course, attractive actors sell movies. However, members of LGBTQ+ are often forced to a standard of desirability to achieve social acceptance, more than straight, cis-gendered people. Hence, when we understand the higher standards applied to LGBTQ+ people, it is critical to ask: do we only extend our empathy to these characters because they’re attractive?

Juxtaposed against the other queer characters, A-Han and Birdy stood out as conventionally attractive and ‘normal’ members of society, who could easily hide their queerness if they wanted to. Notably, this difference in treatment could be seen during the intimate scene between A-Han and an older, gay man. Edward Chen had mentioned that the scene was to express A-Han’s struggle with his sexuality and his inability to express it. However, when this scene played during our Netflix Party’s session, it triggered shock and even disgust from a few viewers. Some referred to the old man as a “pervert”. It is interesting to observe how viewers react differently towards the old man, who was not conventionally attractive. This brings up the question: Why is an old man expressing his sexual desires shameful or disgusting? What does this say about our attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people? Are they only acceptable if they’re, frankly speaking, hot?

The other queer characters, including the old man and the bullied student, were severely underdeveloped. The other characters were often only used as props to portray the perils of being ‘out’. They had no backstories and were one-dimensional. Most of us felt that these characters were not given enough screen time. While a valid critique, it might have been in the director’s intention to do so. By blurring the other characters out, we are pulled into the lives of A-Han and Birdy, enveloped fully in their conflicted love story. However, it is still a good question to ask whether this story is even needed. While an internationally acclaimed movie, we are not short of gay movies with pretty boys as their main characters. If we want to talk about representation, shouldn’t our conversation include the atypical, non-conventionally attractive LGBTQ+ members? Does this movie just present yet another, over-done, high-school romance with socially acceptable gay characters.

However, we also considered how most of us expect LGBTQ+ films to be explicitly political. While we discussed the lack of accurate representation and desirability factor, one of us raised a point about how we often expect LGBTQ+ movies to be politically charged. This expectation restricts creativity. As a semi-biographical movie, shouldn’t we prioritise integrity over representation?

Another discussion point that was brought up was that the actors are straight in real life and whether casting should take this into account to accurately represent queer characters. In Taiwan, few gay actors are openly queer, which severely limits the choices for these roles. We again seem to place stringent expectations on what we believe is a ‘good’ queer film. Why can’t a queer movie simply be about, admittedly cliche, love? Shouldn’t we leave room for creatives to contribute to the art without being bound by the need to be political?

Your Name Engraved Herein is a no-frills, simple showcase of young love. The disappointment in the movie stemmed from us wanting more, our palette already bored from the numerous LGBTQ+ movies that have dealt with the same subject matter. This movie moved us but it was far from groundbreaking. Despite being a beautiful movie, it left us yearning for more.

Conclusion

Overall, this film’s grossing numbers might not be a good indicator of it being a match for the gold standard, but it is sincere and well-thought in its production. It's heavy themes involving politics and religion are pillars in the epic genre this film is unavoidably a part of. However considering that Taiwan is now one of the more accepting societies, with same-sex marriage legalised, the film falls short to its potential in being a strong queer film. But isn’t it a constant journey to make more accurate and important films as society grows? Either way, thie film was an important springboard for us to discuss these important issues and got us thinking about other queer films that we should constantly expose ourselves to in order to understand the subject matter more.

Onward!

Here are some shows to check out if you want to put our analysis of Your Name Engraved Herein into deeper thought:

● Heroin/Addicted (2016) - Mainland Chinese television series

○ Fun fact: The 2nd season was halted by the Chinese government after the immense popularity of the 1st season.

○ Still one of the most prolific picks in the LGBTQ and Boys’ Love genre.

○ Heroin/Addicted demonstrates how the Your Name Engraved Herein might have undergone a different type of response when taken under a more hostile context as opposed to Taiwan’s more accepting environment

● Dark Blue and Midnight (2017) - Taiwanese television series

○ Textbook example of a typical Boys’ Love series that mostly appeals to women

○ Both leading males are typically handsome men

○ Melodramatic, and contains the distinct elements of a soap opera, of which their taboo relationship is more of a plot device to generate drama rather than send a compelling message

○ Their chemistry is subjective, as most of their romantic moments play out on screen as more for fan service rather than for character growth

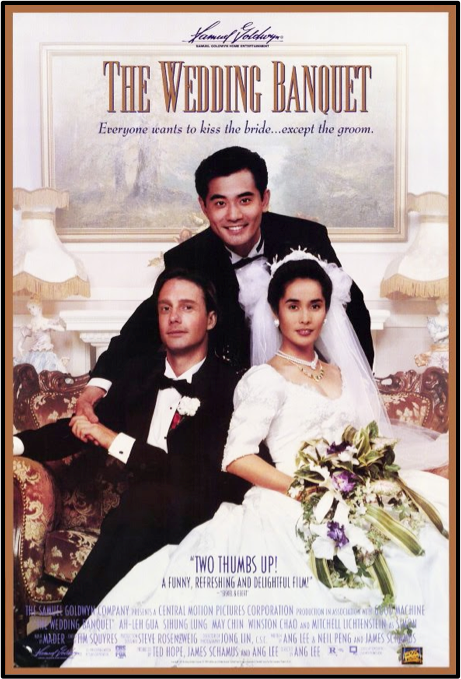

● The Wedding Banquet (1993)- A Taiwanese and America co-production on an American-Taiwanese man pressured into marrying his beard while still maintaining his gay relationship, that results in comedic hijinks and situations.

○ An Ang Lee directed film, before he went on to direct the internationally renowned and Oscar-nominated queer film, Brokeback Mountain

○ An early example of a film that centred on queer love (not just for throwaway jokes) between two men that managed to break into mainstream viewing

○ Was selected as Taiwan’s foreign language film submission for the Oscars

○ To this day, the film is still being analysed and discussed, in both LGBTQ and immigrant media circles