Lou Ye: Inhabit the Cinematic Setting

Lou Ye: Inhabit the Cinematic Setting

Lou Ye may well be the only Chinese sixth-generation director who remains profoundly relevant in today’s international art scene. While contemporaries like Jia Zhangke, Wang Xiaoshuai, and Ning Hao continue to produce a steady stream of works for global festivals, Lou stands out as the sole figure who intentionally evolves his cinematic language to align with each era and spatial context. Over decades of cinematic practice, Lou has described his approach as being “attached” to the times, making his cinema inseparable from the fabric of socio-historical reality. Through an examination of Lou’s past works, including Suzhou River (2000), Summer Palace (2006), and his latest piece, An Unfinished Film (2024), alongside insights drawn from first-hand observations at this year’s Singapore International Festival (SGIFF), this article seeks to reconstruct and explore Lou’s philosophy of cinematic reality in his creative process.

Lou Ye was part of the Silver Screen Awards Jury at the 35th edition of the SGIFF, where his latest work, An Unfinished Film, was prominently featured in the Horizon section. He also delivered an insightful panel talk in person (In Conversation: Lou Ye) as part of this year’s program. Tickets for both the film screening and the panel discussion sold out immediately upon release.

An Unfinished Film received the Audience Choice Award on December 8th at this year’s SGIFF and is scheduled for a special repeat screening on December 14th.

In the panel talk, Lou admitted with refreshing frankness that the environment is both an obstacle and a driving force for his creative process. He passionately embraces any uncertainties it entails, remarking that “The charm and vitality lie beyond design (魅力与生命力在设计之外)”. Meanwhile, the enigmatic and unpredictable censorship system enforced by China’s State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) – described by Lou in an interview as “no one knows the exact boundary” (Cinephilia, 2020) – has remained a constant presence throughout the careers of sixth-generation directors. For these filmmakers, the shifting political climate is an inescapable reality they confront time and again. Politics, therefore, is not just a backdrop to their cinematic reality but a force deeply internalised as an integral part of their artistic expression.

Though individuals may have their own opinions on Chinese censorship, we’d like to look past any value judgements but recognise it as an inescapable part of reality that the six-generation director must contend with – actively shaping their worldview in ways that transcend their individual will. Any one director may also respond differently to the political landscape at various points in time. For instance, to meet the SARFT’s standards, Lou made over one hundred cuts to secure the release of The Shadow Play (2018) (Cinephilia, 2020), illustrating a cooperative dynamic between creative vision and ideological constraints. In contrast, in works like Summer Palace and An Unfinished Film, Lou defiantly bypassed censorship altogether, opting to release the films overseas without obtaining official approval (the Dragon Certificate, or 龙标).

The unique political sensitivities of Chinese authorities shape Lou’s perception of reality in at least three distinct ways. First, recognising that reality is inseparable from politics, Lou excels at uncovering the political undercurrents embedded in daily experiences.

*Spoiler Alert: The next paragraph may contain minor plot details from An Unfinished Film (2024). Skip to the next paragraph if you would like to avoid any spoilers!*

In the climax of An Unfinished Film, Lou designs a scene where the crew members in the story attempt to break out of their quarantine rooms on New Year’s Eve, only to be immediately forced back by the guard – a moment that evokes the feel of a micro upheaval that is much valued in the Leftist political philosophy.

*Spoiler End: It’s safe to proceed from here!*

Intriguingly, the entire scene unfolds to the backdrop of the viral Dou Yin (Chinese TikTok) song Huohong de Sarilang (火红的萨日朗). This song, usually associated with a lower-culture genre of music considered unsophisticated, outdated and rustic (“土”), yet resonates with the general public while being dismissed by elitists. At the same time, its lyrics metaphorically celebrate a unique flower species, extolling the non-restrained and carefree nomadic life of Mongolia. Both quarantine and the song were highly topical in China during the COVID era, but the juxtaposition of the two amplifies the tension, creating a moment that authorities might unmistakably interpret as sharp criticism.

Second, owing to the inseparability between politics and reality, Lou’s work is never intended as a deliberate reference to or commentary on contemporary politics. In the post-screening Q&A after the screening of An Unfinished Film on December 3rd, Lou humbly confessed that such considerations rarely cross his mind during the creative process. Instead, his focus lies entirely on portraying reality, with politics emerging incidentally as part of the broader reality he seeks to depict. During the production of An Unfinished Film, he even instructed his crew to “save the videos online”, not for any political purpose but simply because “it will be fun to watch years later”, much like replaying a family VHS tape at a gathering.

Third, as Lou’s primary focus is on a broader reality, his work prioritises overall dramatic tension over local political tension. He aims for heightened subjective sensibility rather than a chronological recounting of historical events. As a result, his films are often intensely saturated with emotion, pushing his portrayal of reality to another extreme. Simultaneously, Lou’s work presents two contrasting interpretations of reality: one that is radically subjective, where private stories evoke profound sentimentalism, and another that is radically objective, and faithfully assumes the role of a socio-historiographer. As Ma Da in Suzhou River puts it: “My camera never lies (我的摄影机不撒谎)”.

As Lou himself aptly describes, this duality is mediated by a third presence, serving as a bridge between psychological reality and socio-historical reality. In Suzhou River, this presence takes the form of Ma Da’s reflective narration; in Summer Palace, it is Yu Hong’s introspective monologue as she reads her diary; and in the recent An Unfinished Film, it manifests as the digital interface of WeChat or Dou Yin projected onto the silver screen.

However, Lou’s cinematic reality cannot be confined to his distinctive approach to accessing socio-historical reality through film. His work extends beyond this framework, constructing a hyperreality within the process of film production. This concept is best exemplified in Lou’s working methodology. He describes building a “realist” scene as a technical process that involves carefully predicting possible interactions between actors and their surroundings. This requires close collaboration with the art department, enabling the actors to fully “inhabit the setting (生活在拍摄环境中)”. Lou’s aesthetic of reality is not metaphorical; he physically constructs scenes that allow actors to move freely and naturally within them.

On the one hand, the observing camera is deliberately excluded from the rehearsal process, positioning it as external to the hyperreality. On the other hand, this absence allows the camera to seamlessly integrate into reality during actual shooting, capturing events as they unfold – spontaneous and uncalculated, driven by pure observation. In essence, Lou’s hyperreality can be succinctly defined as a dramatic reality enhanced by the presence of an observing camera.

Perhaps the most essential element of Lou’s cinematic reality is his ever-evolving linguistic features. His film language is always ad hoc, resisting any form of fixation. In Suzhou River, the rapid succession of shots in the opening sequence, captured from a moving boat, not only establishes the geographical context but also creates a chaotic atmosphere for the unfolding plot. In Summer Palace, Lou shifts his focus to mise-en-scène, adapting to the more compact and complex spaces of dormitories and classrooms. By contrast, in An Unfinished Film, Lou is compelled to abandon elaborate mise-en-scène and long takes, as most scenes are confined to a single room. This constraint pushes him to adopt a simpler and more concise visual language.

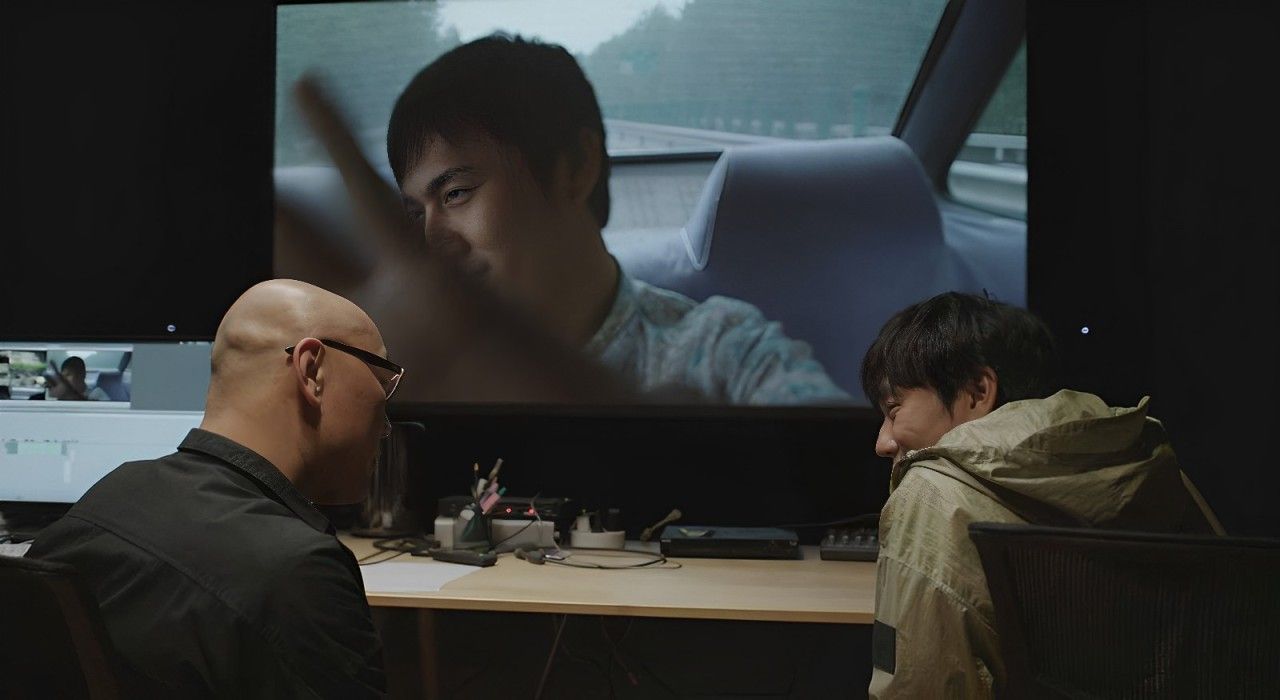

At the same time, the evolving method of histography translates into distinctive approaches to image acquisition. Lou describes his monitor room during the production of An Unfinished Film as “the cockpit of an aeroplane”, reflecting the diversity of tools he deploys, including cinematic cameras, portable cameras, digital video (DV) cameras, phone cameras as well as found footage from Dou Yin. To insist on the legitimacy of a single film language, he argues, is to adopt a narrow perspective. Instead, the pressing question for Lou is: how should cinema respond to new interfaces and the evolving presentation of visual images? He observes that while phone screens have been ubiquitous for over two decades, their representation in cinema remains underdeveloped. Few filmmakers, he contends, have refined this as a legitimate part of film language.

Lou, in essence, is a director who evolves seamlessly with his time. His poignant sensitivity to reality and playful reinterpretation of his immediate surroundings remain as sharp as ever as he enters his 60s – a quality vividly evident in An Unfinished Film. This enduring vitality is, in itself, a remarkable gift from a masterful filmmaker like Lou to the mundane world.

A limited number of tickets for the repeat screening of An Unfinished Film on December 14th are available for purchase on SISTIC: https://ticketing.sistic.com.sg/sistic/booking/sgiff2024.

Reference:

Cinephilia. “娄烨访谈:用电影抵抗空间记忆的消失.” Cinephilia, May 7, 2020. https://cinephilia.net/75691/.

---------------------

About the author: An omnivore in film, literature and philosophy.

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.