The Right to Rest: Jow Zhi Wei’s 'Tomorrow is a long time'

The Right to Rest: Jow Zhi Wei’s 'Tomorrow is a long time'

On the grey Friday afternoon that precipitated the astonishing spell of cool in January 2023, Jow Zhi Wei arrived in step with his debut feature Tomorrow is a long time (明天比昨天長久, 2023). Like Meng, the adolescent at the heart of his film, he has just emerged from the vague jungles of post-National Service reservist duty (which he can’t say much about because of the classified nature of his unit), and was feeling a little dazed by the re-entry into the city. I asked how he's feeling about the film, and he smiled. He was editing it until recently, and still feels too close to it but was “curious to give it some time and take a step back, then watch it again later”.

Set to premiere in competition at the 73rd Berlinale, the film stars the acclaimed Taiwanese actor-director Leon Dai of Your Name Engraved Herein (2020) fame and Singaporean newcomer Edward Tan. They play a widowed pest exterminator named Chua and his sensitive son Meng respectively who struggle to maintain their dignity amidst the harsh socio-economic structures imposed on them. Between the exhaustion of keeping up with the lifetime of labour that accompanies the working class in Singapore and beyond, the failure of bodies to keep up with the demands of one’s occupation and the resulting insomnia borne of the adrenaline needed to keep going or die, Tomorrow is a long time evokes in its title a simultaneous promise. First, that the moment of anguish will afflict itself on the body, demanding to be tended to—and it is a tending to an insistent grief that must be addressed. Until it spends itself, at which point the stunning, expansive possibility of a future reasserts itself in infinitum.

As we settle into the offices of Akanga Film Asia with Jeremy Chua, founder of Pōtocol and one of the producers of the film, we get to talking about the cyclical nature of the working class and its pointless extraction of labour. In Chua’s work as a pest exterminator, he is dependent on the business owner for assignments and so takes on any shift offered: what if, as quickly as they came, the flow of orders suddenly subsided? He is shown fumigating a shipyard, an abandoned building and a construction site at night. Each time, the fog of fumigation dissipates into the air, leaving him all alone in a desolate landscape gasping for breath. “The father goes to all these remote places to do his job and works very hard, but these places are completely empty. In that sense, [who is it for, and] what is his purpose?” Zhi Wei says.

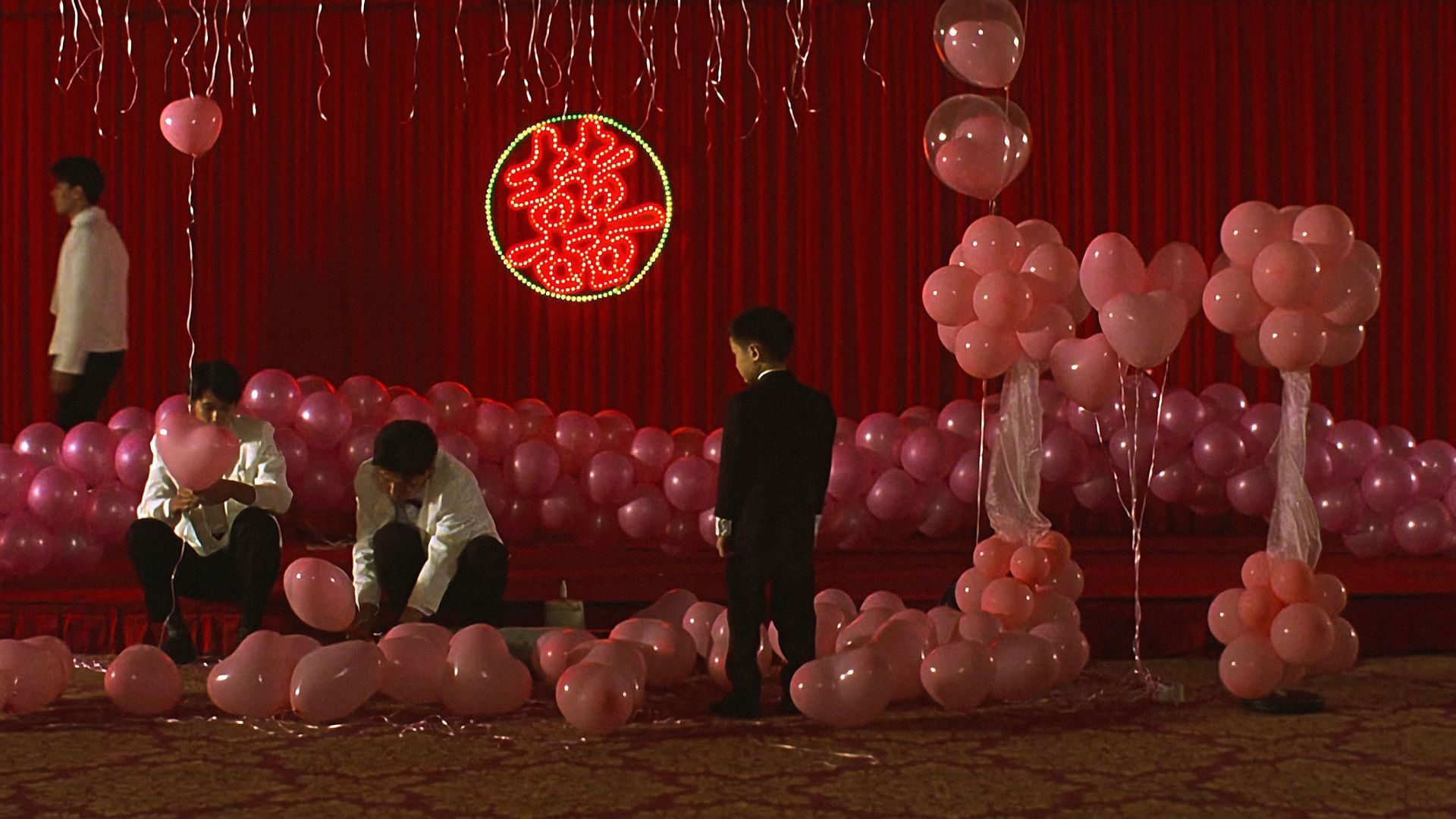

Courtesy of Russell Morton

At the end of each workday, Chua returns home to his Meng, but doesn’t rest to give his body time to recover. Instead, where Meng’s hours in the day are rigidly tabled by school, it is Chua who regulates when he should eat, exercise and sleep outside of school. Zhi Wei points out that the film begins with Chua waking Meng up to complete a prayer in front of the altar table, effectively disrupting his rest. He inadvertently imposes his insomnia on Meng.

To speak of its portrayal of masculinity feels almost trite, for Chua fills in domestic duties without any tortured sense of how it infringes on his portrayal of being a man. No, his work is far too laborious and exhausting; he is merely focused on living each day after the next. What does come up is a fractured sense of self, particularly in Meng, whose questions to his father about his own parents are met silence. In yet another instance, Chua however unknowingly, imposes his aimlessness on his son, whose understanding of his lineage is at best, murky, disrupted by death and illness. It makes sense then that while the violence of his bullies is overwhelming in its brutality, it is also seductive in its easy brotherhood—as if it were an exclusive fight club with membership to an abandoned swimming pool—which he yields to.

How do we break out of what seems inevitable? What would it look like if these dictations of time were removed and the child was left to their own devices? “I’m interested in the aspirations of the children, their dreams and hopes. They want more, and you can see them grasp for something more. I don’t think it’s something the earlier generation had. If you think about our parents, they might have hopes and dreams but they never had the opportunity to go and get those things.” Zhi Wei pauses.

“Maybe it isn’t so much about dreams. I think what I’m trying to find is respite for the characters. These small, very brief moments of respite.”

Courtesy of Russell Morton

In his short film Outing (2009), an elderly man addled by symptoms of dementia takes his orphan grandson out to roam about languidly, as if to forestall its inevitable end. On another note, the stakes in his next short Waiting (2010) are immediately evident as the film’s grieving widower and his son face homelessness should the former fail to gather enough money for the month’s rent. If Outing and Waiting were largely driven by the wills of the caregivers of young children, Tomorrow is a long time enacts the converse by uprooting Meng and transplanting him in another geography altogether in that coming-of-age moment that all Singaporean boys go through in National Service. Away from familiar structures and inundated with new sensations and experiences, Meng begins to live life on his own terms and live closer to himself. It ties up an unofficial and loose trilogy centred on boys and men reeling from the loss of central familial figures in their lives.

I note that apart from After the Winter (2014) which extrapolates the isolation of an elderly couple sequestered in the countryside of Taiwan, his films tend to the relationships between fathers and sons. Was there a reason for this?

“It was probably through a sense of…” Zhi Wei trails off.

He starts again, “The problem with me is that a lot of my stories are very personal. My dad is not… well, let’s put it this way.”

Death has always kept itself in his purview. The loss of the grandmother who raised him when he was still growing up was soon followed by his father’s illness, who had himself looked after his father for the same illness. The possibility that he too, could be an unwitting inheritor of the illness became a point of fixation for Zhi Wei. “It was a question about whether the life he was living was a life that had already been set for him. Where he has no choice but to go on because that was the life of his grandfather and his grandfather’s grandfather and so on,” says Jeremy.

Let us not mistake the personal for the autobiographical. The plane of fiction allows for an ethical inquiry into the unsayable: how does one begin discussing an inheritance over which your elders have no control over, that brings no value but effectively reduces your quality of life? Jeremy notes that at the Berlinale Talents Project Market, producers (and funders) from all over the world were taken by the notion of lineage in Tomorrow because it “captured an intangible understanding of what home and ancestry mean to one’s identity,” resulting in the Singapore-Taiwan-France-Portugal co-production.

It’s not all melancholic though. When Zhi Wei told his mother he wanted to make films, her response deviated from the script of the perennial parent’s lament for their child’s impending economic demise. Instead, she noted that his maternal grandfather too loved movies, and he was well within the right to try his hand at filmmaking. Her response was staggering in light of his family’s financial circumstances, but that bit of familial resonance was enough for her. “My maternal grandfather was a labourer. You can imagine how tired he was but the open-air cinema was a must for him to go to everyday after work. It was a solo activity that he did for himself,” he says.

He has gone about making movies with the same steady resolve that his grandfather went about to the movies and his mother accepted his announcement. His first foray into filmmaking saw him cold calling production houses to pitch his stories before he went to The Puttnam School of Film at Lasalle where the success of Outing and Waiting on the film festival circuit—premiering at the San Sebastian and Busan International Film Festival respectively—gave him the confidence he needed to tell the stories he wanted to tell, even if his lecturers in school weren’t sure about them.

He continued his education at Le Fresnoy in Paris where he was mentored by the fiercely independent and celebrated Quebecian filmmaker Denis Côtè (Vic + Flo Saw a Bear). Côtè tells me that Zhi Wei was “passionate about his time at Fresnoy and concerned about his future as a filmmaker” and is “happy he worked hard [so] that his film could enter this year’s Berlinale.” Made during his time at Le Fresnoy, After the Winter was selected to compete at the prestigious Cannes Cinéfondation Selection. In 2014, he was conferred the Young Artist Award, the most prestigious prize for art makers under 35 in Singapore.

His dedication to his craft has also been noted by Fran Borgia, who was attracted to Zhi Wei’s shorts for their “maturity [and how it] all felt very close to me.” They met while working on a project for Ho Tzu Nye’s Zarathustra (2009). “I liked that he was willing to talk about something so personal and intimate. He understood that it would take time to build a strong script at script labs and that finding finances would be a challenge. He had the right attitude and gave all the time that was needed to develop the script and to find the right partners, which was essential.”

In Berlin, we agree to meet at a coffee place in Potsdamer Platz. Edward arrives first after a ballet class, in a short-sleeve shirt and a padded jacket (“I like the cold!”). He is 24 years old and is currently pursuing a degree in Psychology at Nanyang Technological University whilst pursuing acting on the side. At one point, he talks about the fearlessness demanded of ballet when pirouetting and leaping into the air and how he has to overcome it. If it’s present in his dance, it certainly isn’t in his acting. Zhi Wei talks about how it was precisely that “fearless acting” that set him up for “intrigue”, “We saw about 300 actors but after [Edward’s] audition, I knew it was him. On set, he was going up against Leon Dai, a 7-time Golden Horse winner but he wasn’t afraid at all, and that’s important.”

Again, I ask Zhi Wei how he feels today now that he’s in Berlin and the film’s premiere is so close. The same smile: he’s excited, but the “big word here is relieved because I can finally share it with everyone, even my actors and crew.” He edited and lived with it for a year; it’s time to release

Tomorrow is a long time

to the cinema and rest, “hopefully without dreams.”

------------------------------------------

This review is published as an extension of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme organised by The Filmic Eye, with support from the Singapore Film Society.

About the Author: Sasha seeks to reify the fugitive effects of looking through language. She received her BA in 2021 and has worked with HBO Asia, the Singapore International Film Festival and the National Archives of Singapore.

------------------------------------------

About the Movie:

Directed by: Jow Zhi Wei

Cast: Leon Dai, Neo Swee Lin, Julius Foo, Edward Tan, Harry Nayan, Lekheraj Sekhar, Jay Victor

Year: 2023

Duration: 1h 46min

Language: Mandarin

Synopsis: A middle-aged widower whose relationship with his sensitive teenage son in the densely packed spaces of contemporary Singapore slowly becomes unbearable.

Tomorrow is a long time premieres at Berlinale today.