Fishing for Words (SYFF): Lingering Belief in Community

Lingering belief in community: a short commentary and interview with Director Alton Tan

Alton Ron Tan’s Fishing for Words is a compelling short documentary that delves into the daily struggles of aphasia patients and their community in Singapore. Aphasia is a language disorder typically caused by brain injury. To varying degrees, it impairs a person’s communication ability, making even daily conversation a constant challenge. Currently, in Singapore, it is estimated that more than 2,500 individuals are diagnosed with aphasia.

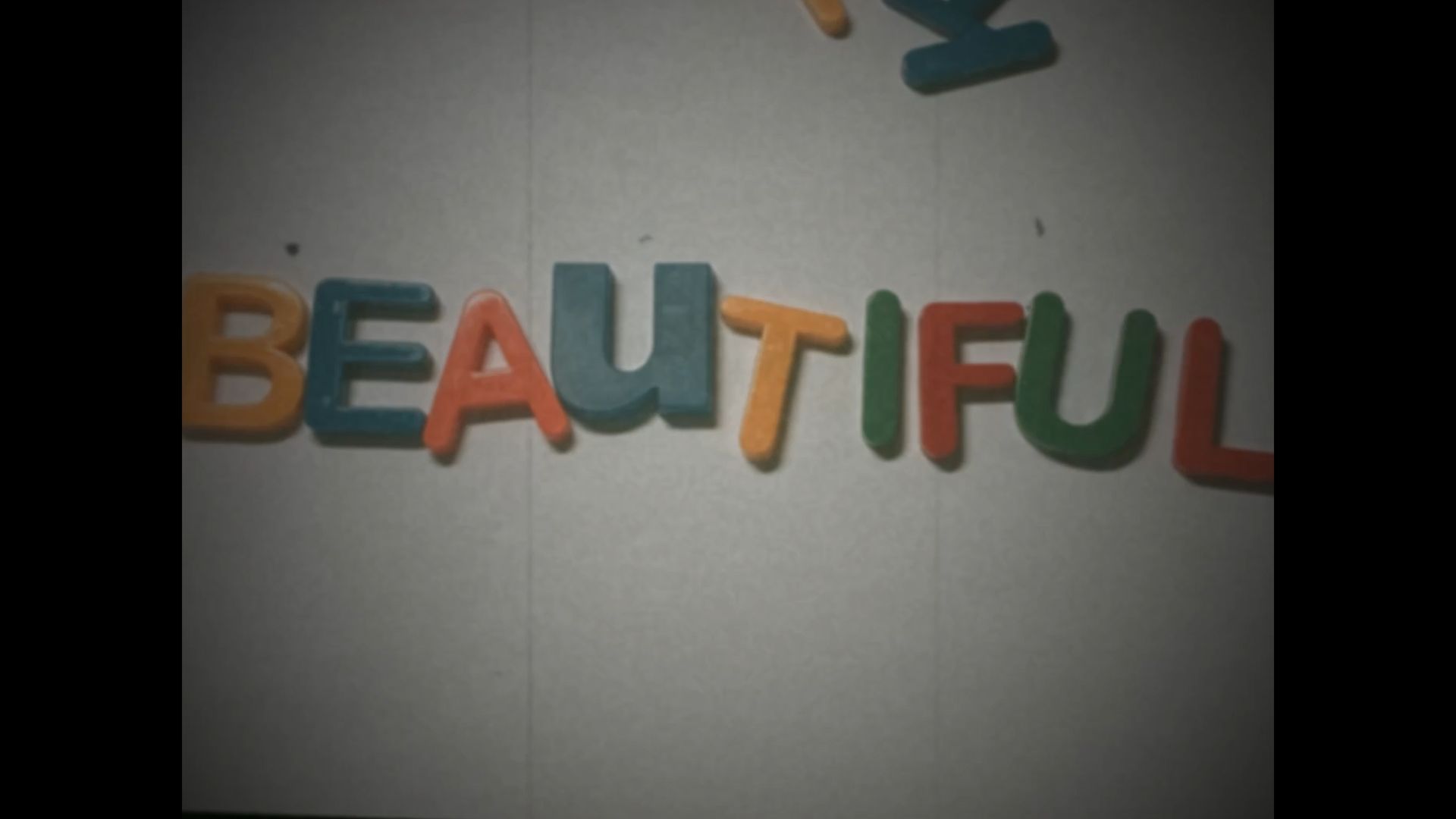

Through his distinctive visual language that deploys striking imagery (or Montage d’attraction, to invoke a jargon from Eisenstein) and the recurrent motif of a children’s toy – alphabet fishing – Alton tactfully draws viewers into the fragmented inner word of aphasia patients and vividly highlights their constant wrestle with sentence construction.

The notion of meaning and cohesion no longer unfolds naturally through the single dimension of sound wave transmission. Alton creatively reimagines and problematises this process through the lens of aphasia, presenting a nuanced sense-making model that operates simultaneously on both auditory and visual levels.

In the unedited interview clips of aphasia patient Sherwin Tang, we witness the arduous labour of meaning-making. At times, meaning eludes us entirely, resulting in miscarriages where sense refuses to reveal itself. More often, the typically straightforward path to “good senses” is disrupted and detoured, leading us, alongside Sherwin, to repeatedly stumble into the rabbit holes of stammering and navigate the labyrinths of disorganised signifiers.

‘Fishing for Words’ was selected for inclusion and screened in the 2024 Singapore Youth Film Festival (SYFF) where it was met with enthusiasm.

Stammering in community

In our initial correspondence, I was entirely unaware of Alton’s neurodivergence. He shared some of his early works, including his dissertation on documentary as a form of activism, along with a few short films and scripts. Two intertwining themes immediately stood out across his works: community and communication.

In the fiction screenplay Budak Bising, the Malay teenager Afiz seeks to escape his family due to a lack of genuine conversation. In the documentary The Other Side a boy reflects on his struggles with finding community and navigating personal disillusionment with a religious group he once belonged to. In Fishing for Words, the themes of disrupted communication and the struggle for integration are unmistakable.

At the same time, Alton’s cinematic world often reveals a persistent hope for community and frank communication. Whether it is the family photo on Afiz’s wallpaper in Budak Bising, the yearning to be part of something larger in The Other Side, or the struggle to reconnect with society in Fishing for Words, these stories move away from the postmodern idea of “activism”, which often questions the value of community and communication. When asked about his view on community and communication, Alton’s answer is simple: “No one can live alone”. But what drives Alton to adopt this unconventional stance on activism? How will he interpret his activism through the lens of documentary filmmaking?

With these questions, I met the 27-year-old filmmaker on a fresh, stormy Saturday afternoon at a cosy bar near his alma mater, LASALLE College, where he graduated last year with a bachelor’s degree in film.

Exploring aphasia

Wenbo: ‘Fishing For Words’ explores aphasia. What drew you to this topic, and how did your initial inspiration evolve during production?

Alton: I originally planned to do a document about my experiences growing up on the autism spectrum part of my undergraduate project. My lecturers, however, suggested that my work should be more aligned with the community.

Around the same time, I came across actor Bruce Willis’ story. Later in life, he started appearing confused and disorientated in films. In 2021, all eight films he acted in that year were grouped into a special category at the Golden Raspberry Awards titled “Worst Performance by Bruce Willis”. It was later revealed by his family that the underlying condition is aphasia, resulting from frontotemporal dementia. Hence, I found some commonalities with my autism condition and aphasia, both are invisible and closely related to communication and language processing.

W: But why language?

A: Words are like currency. It is more essential than ever in today’s world. Especially when your livelihood depends on language, losing that ability makes it incredibly difficult to survive. That’s when I realised I wanted to create a documentary on this topic, but with a focus on something more local. People who suffer from aphasia often don’t receive the empathy they truly deserve.

Empathy and representation

W: What is empathy to you?

A: Empathy, to me, is more like a continuous exercise in understanding what I have compared to others. I have encountered various people from those on the variable ends of the autism spectrum to my current wheelchair-bound colleague. They face challenges I don’t have to deal with, just as I face challenges they might not experience. Empathy isn’t about forcing yourself to fully understand someone else’s experience – but really, it’s about recognising and understanding your differences.

So, it’s all about balancing your inner strengths and flaws with other people’s experiences. It’s not about pitying others or seeing them as weaker. It’s about understanding that we are all flawed in different ways.

W: Do you think we have done enough to portray such empathy in our visual culture?

A: No. Let me give you an example. In the 2022 National Day Parade, there is a segment featuring disabled individuals in wheelchairs singing a song. When filming the segment, many cameras, focused on the wheelchairs or visible impairments rather than the individuals’ faces. While it gives you context for their condition, I don’t think it’s enough. Not all disabilities are visible, like those involving wheelchairs; some of them can be just entirely invisible.

W: So you approach this differently.

A: I want to show people that people have agency. They are always actively doing something to regain that sense of normality. At least, that’s what I’ve experienced in my own life.

W: How does that change the way you view yourself?

A: I did not find out I was on the autism spectrum until I was 16. My brain processes things more slowly, and I struggle with complex topics. I had to drop my mother tongue in primary school because I wasn’t progressing in language. I was also bullied in school. I was unsure how to define my identity.

But over time, I realised I needed to stop feeling sad or wishing life had been different. I had to start doing something about it.

Documentary as activism

W: In your dissertation, you advocate for documentary as a form of “activism”. Do you consider it political?

A: No, I don't see it as political. If it were, I’d be encouraging donations to the organisations or lobbying the government to take action. But that’s not my intention. I don’t want to force anyone to make a choice. At least I don’t believe it’s about choices in the way, say, a presidential election is. If I were creating something to lobby the Singapore Parliament for more support for people with disabilities, that would be fine – but it’s not what I want to do.

W: So you see it as something personal – a direct exchange between you and your audience.

A: Yes. For my audience, if they feel engaged but don’t know where to take action or aren’t sure if they even want to, it’s okay. What matters is that they become aware – that they recognise these struggles and uncertainties in life. If my films help them understand the value of empathy and the flaws inherent in being human, that is more than enough. For me, it’s also about finding a sense of closure.

W: It’s a therapeutic form of activism.

A: We have been showing the depressing state of the world, but I believe that activism is about inspiring hope despite humanity’s flaws. I want people to be moved in a way that feels casual, not tragic. Right now, it’s about spreading more love and less hate.

W: Give us three recommendations for documentary films

A: Dear Zachary by Kurt Kuenne explores the flaws in Canadian custody laws. Procession by Rober Greene talks about the religious abuse and trauma in the Roman Catholic Church. Marwencool by Jeff Malmberg shows a man’s struggle with amnesia.

Alton Ron Tan’s

Fishing for Words

is available for streaming at:

https://vimeo.com/1038473437/9addab9d4a

---------------------

About the author: An omnivore in film, literature and philosophy.

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.