Film Review #36: CHILDREN OF THE MIST

Film Review #36: CHILDREN OF THE MIST

*This film review may contain plot spoilers, reader discretion is advised.*

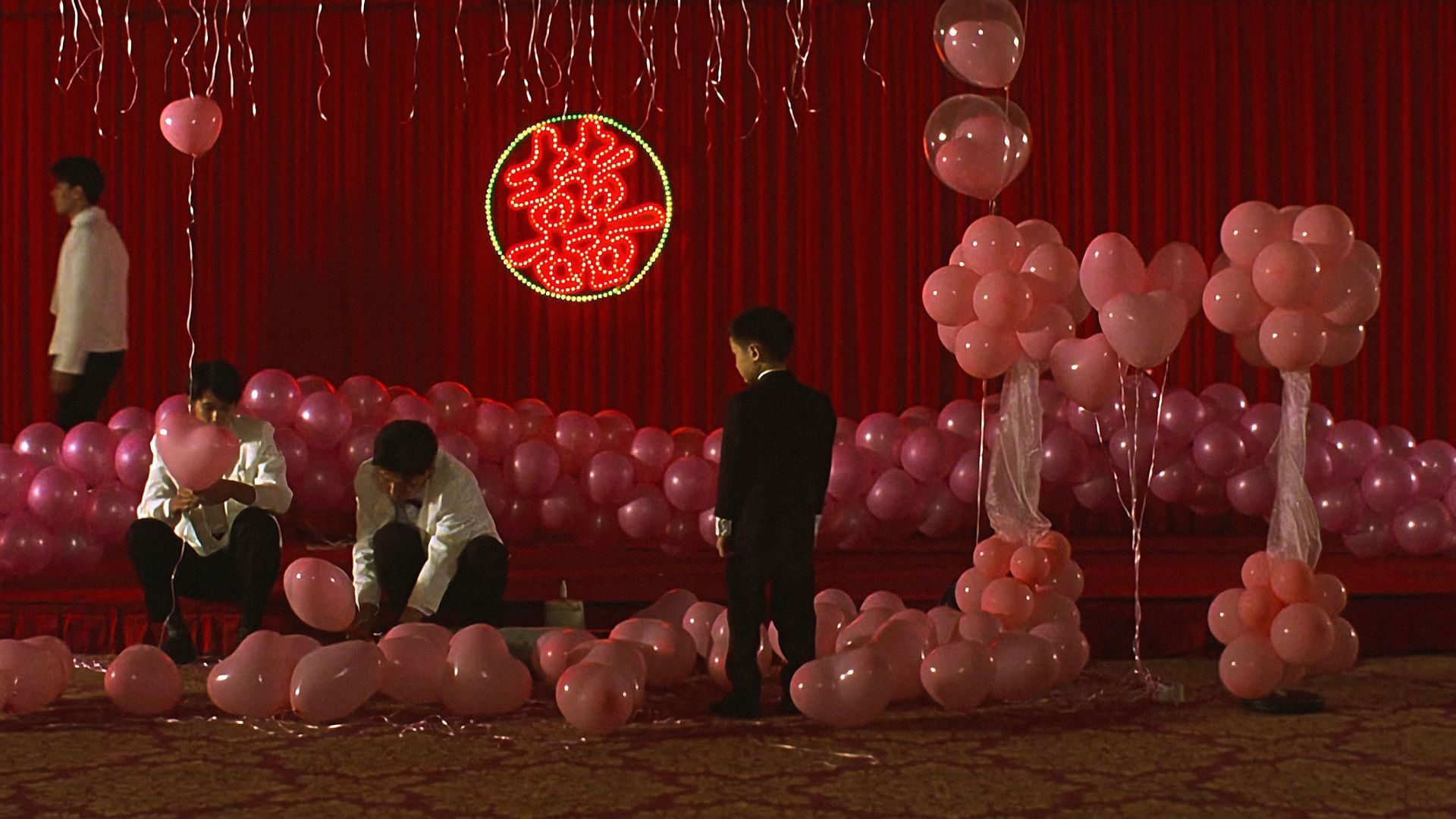

Photo credit: Cat & Docs

How do you do justice to the precarious story of a young girl’s life?

It’s the surprisingly difficult question that director Hà Lệ Diễm grapples with in her documentary Children of the Mist (and, in all honesty, this writer with her review). The first Vietnamese film to be shortlisted for the Documentary Feature Film category at the Oscars, Diễm’s film follows the story of Di, a 12-year-old Hmong girl from the foggy mountains of rural Vietnam and her struggle with the controversial practice of “bride kidnapping” within her ethnic community. Strikingly honest yet carefully intimate, the film is a noteworthy look into the systems and traditions that envelop Di and her entire community, a mist that seems impossible to disperse but cannot remain.

Children of the Mist subtly confronts the Hmong tradition of “bride kidnapping”, a process of marriage by abduction that takes place during the period of Lunar New Year celebrations. Like every “good” documentary, Diễm’s film appears candid and even-handed in the portrayal of its subjects; in one of its first scenes, the camera follows a young Di and her friends as they frolic around a mountainside, playing a game that is later revealed to be “kidnap the bride”. It is this disarmingly blasé perspective towards a very plausible threat that the film then carefully and quietly sets about dismantling.

The strength of the documentary lies unequivocally in the care that Diễm has for her subject, and consequently, how Di and her family are represented on screen. Children of the Mist was the product of a three-year stint that Diễm (herself ethnically Tay) spent living amongst the Hmong in Northern Vietnam, frequently visiting Di’s village for weeks at the time. The bond between filmmaker and family is obvious – from the glimpses of their daily life in all its profane sincerity to moments of quiet reflection, Diễm’s handheld camera is somehow a natural presence in the family’s little wooden farmhouse. It is a device for listening rather than narrativising, and so we learn of Di’s romances and dreams of her future, her mother’s own experience of abduction, and her father’s alcoholism, all without judgment as we watch her angsty teenage years kick in.

This leisurely documentation of Di’s life pivots at a New Year’s celebration, as she walks away with a young man named Vang who promises not to kidnap her. The objectivity of the camera begins to waver, literally, as Di’s figure retreats into the distance. Yet, this is Di’s bride-kidnapping. As the audience reels from Vang’s broken promise, we find that this fissure in objectivity only grows wider as it takes on the task of documenting this shocking turn in Di’s life. We approach with increasing skepticism the families’ pleas for Diễm to refrain from interfering as it was 'not their place' and their resolute haggling over Di’s dowry. Interspersed with interviews with Di (who muses on her own immaturity) and Vang (who shyly admits to being out of his depth), the film completes its work of dismantling the tenuous gloss of tradition, revealing the economic dependency that lies beneath the practice of bride-kidnapping.

It is also the moment where Diễm breaks the sacred objectivity of the documentary filmmaker to–however briefly–respond to Di’s desperate cries for her help that we discover some kind of an answer to how one can do Di, or other girls like her, any justice. In the split second of hope that Diễm’s intervention sparks as the younger girl is forcibly dragged from her home, it becomes crystal clear that offering our unconditional protection to these girls, even in the face of an approaching and relentless mist, is the most important thing we can do for them. Children of the Mist is ultimately a clarion call to its audiences, urging them to re-evaluate the neutrality of ethnographic documentation and see further into the lived experiences and complexities of tradition and loss.

——————————————————————————-

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, organized by The Filmic Eye with support from Singapore Film Society and Sinema.

About the Author: Goh Yu Ke is an English Literature and Film Studies student at the National University of Singapore. When she’s not reading or busy with school, you can find her working through her watchlist of 1940s screwball comedies.