Film Review #17: BULLET TRAIN

Film Review #17: BULLET TRAIN

*This film review may contain plot spoilers, reader discretion is advised.*

Film still from Bullet Train

Bullet Train is fun, action-packed and bloody. Its action sequences remind us of the films of Jackie Chan, where the fighting is goofy yet well-choreographed, with characters using items on hand to create slapstick and acrobatic stunts—you’re guaranteed to laugh your a** off.

Brad Pitt is brilliant as Ladybug, the “main” character in the film (we’ll get into that): The humour from his character is compatible with the goofy stuff happening around him. Aaron Taylor-Johnson also puts up a great performance as Tangerine, a humorous English bloke who isn’t afraid to get his hands dirty to get the job done.

Bullet Train’s storyline is witty but also easy to understand. The self-embracing of the story’s ridiculousness makes it distinct in the sea of action movies and all the more joyful to watch. Everyone seems to have an equal workload in pushing the story forward and the backstory of the vengeful villain really holds enough weight for some sort of sympathy to grow in the viewers.

Film still from Bullet Train

Bullet Train is also overly funny, though filled with some jokes which may be hit or miss. The randomness in the movie draws chuckles from the audience who soon enough become confused. For instance, Brian Tyree Henry’s character, Lemon, has a weird obsession with ‘Thomas and Friends’, but the flashback to his childhood shows him watching football instead. This frayed connection between the movie’s humour and emotions for its characters shows up often—one emotionally heavy scene has its payoff stunted because we simply don't relate to the character enough.

Sandra Bullock plays Maria Beetle, Ladybug’s handler, whom we regularly hear, but don’t see throughout the movie. Her only appearance is a 10-second cameo that does not add value to the film. Her sudden appearance is awkward and leaves viewers more confused than surprised.

Other actresses starring in the film are Joey King (of the infamous ‘Kissing Booth’ movies) and Karen Fukuhara. King plays The Prince, whose potential as an interesting character goes out of the window as her character suddenly disappears in the third act. Meanwhile, Fukuhara has a very minor role as a train attendant with only a handful of lines in the film. It would have been more entertaining if these two actresses got more screen time—well, they are already on the train after all.

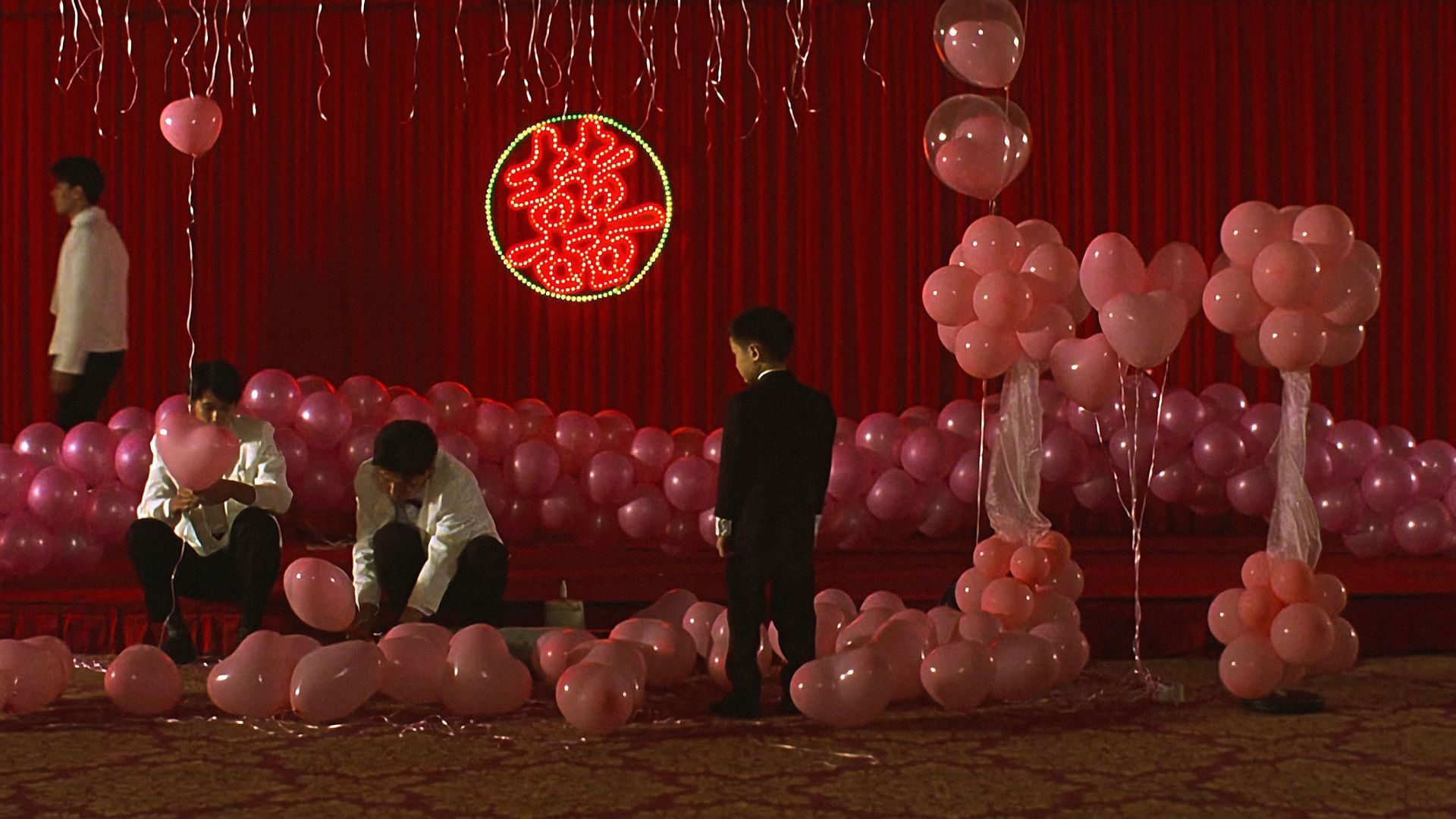

Film still from A New Old Play

The subversion mainly comes in the way it depicts the very turbulent history of China during the 20th century. Qiu’s journey begins before the Chinese Civil War, we see him and his family push through the hardships of the Great Leap Forward, and ends at least near or after the end of the Cultural Revolution. This “backdrop” of a ruthlessly changing China has appeared before, with panellist Fu Qiang (NUS Professor) bringing up clear comparisons to Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine. But compared to that movie’s explosiveness, A New Old Play is much more emotionally controlled. Turmoil, political commentary, and famine are depicted in no small part with the revolutionary element: humour.

And this movie is indeed full of humour. In fact, I was pleasantly surprised at how funny it was at times. While it never fully disregards the horrors of war and political prosecution, a lot of that is coated with gallows humour and spot-on comedic timing by its cast. Ox-Head and Horse-Face, two figures in Chinese folklore that more often than not are regarded with a sense of seriousness due to their roles in the afterlife, are portrayed here as low-level, scruffy officials that serve the bureaucratic office of the underworld. One of the jokes involves Qiu receiving a lump sum of money in the underworld, burnt for him as offerings, which he uses to bet in mahjong. It is this clear transgression-by-comedy of long held importance to these figures and history that make A New Old Play such a breath of fresh air, and I cannot help but wonder if the very warm reception that it had during the screening was indicative that this was something the people didn’t know they wanted.

This culturally niche yet finely executed vision ultimately ties back to Qiu, the character, and Qiu, the director, themselves. This is a very personal work, a fact that was all but confirmed when director Qiu elaborated on his own reasons for making this film. He reaffirmed Ms. Ting’s comments on the intentional “theatre” nature of the film, and explained that the movie was based on his grandfather’s life as a Sichuan opera troupe actor. Sichuan opera, as he stated it, holds a deep connection to the working class of the Sichuan people, with the role of the “clown” being one that holds a particular distinction. This is reflected through what Qiu, the character, goes through in recollecting his life. The changing times dictate what sort of “clown” he is allowed to be, and what can be made fun of; a representation of the populace forced through politically reinforced change. The commentary is blatant, but nonetheless effective underneath its veneer of comedy.

——————————————————————————-

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, organized by The Filmic Eye with support from Singapore Film Society and Sinema.

About the Author: Weng Leong prides himself in having watched Parasite before it won Best Picture in 2020 and will gladly mansplain to anyone why Memories of Murder is Bong Joon-Ho’s best film. He is most often seen talking about film and politics instead of actually studying at SMU.