Film Review #73: AFTERSUN

Film Review #73: AFTERSUN

*This film review may contain plot spoilers, reader discretion is advised.*

Imagine you are looking at a painting. In close proximity, the intricate details frame your field of vision – a modicum of a bigger picture that has yet to be seen. When you take a step back and steep into the landscape’s vast expanse, you will unearth something remarkable hidden within the canvas – the profound sincerity behind each brushstroke and the tender vulnerability of a painter’s soul. This is how one should approach Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun, embracing the film’s striking epiphanies and haunting heartbreak.

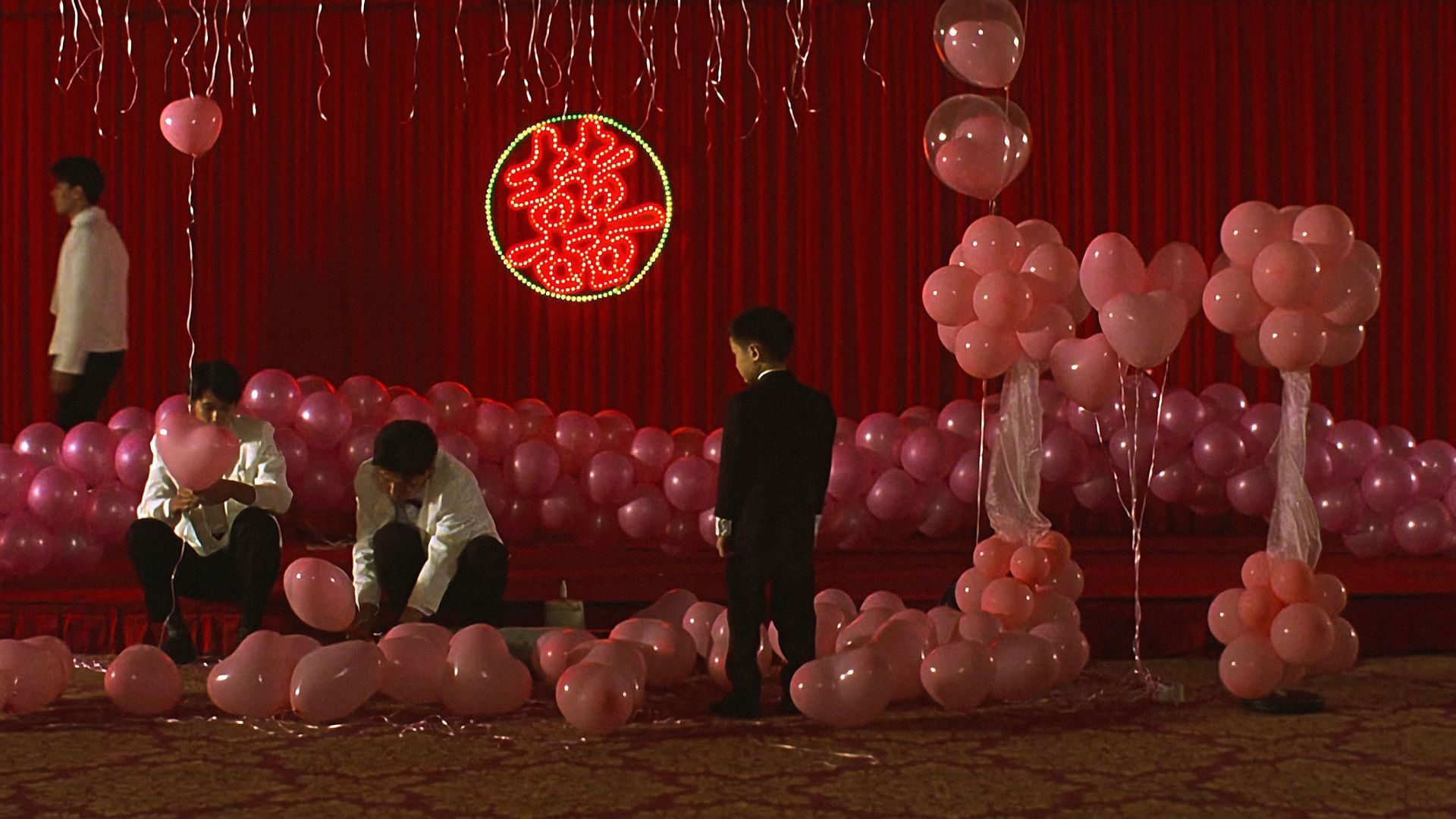

First-time feature film director Charlotte Wells stuns audiences worldwide with a mesmerising debut feature of a father-daughter vacation weaved into an emotionally riveting coming-of-age drama. 11-year-old Sophie (Frankie Corio) and her divorced father, Calum (Paul Mescal) spend her school’s summer holidays at a beach resort in late 1990s Turkey. Filtered through the lens of a hand-held camcorder, the now-adult Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall) reminisces her fleeting interactions with her father on this vacation, offering a glimpse of an endearing past she longs to understand. A collection of haphazard memories and fragments of reality painted with a hallowing undertone of Calum dancing in a strobe-lit nightclub brings us through the nostalgic complexity of Sophie’s inner world.

Aftersun premiered at the Cannes Film Festival brimming with critical acclaim but alas, such sentiments were not echoed across the board by some film critics. The film’s slow pace and non-linear timelines felt sluggish and dreamlike amidst A24’s conventional three-act narratives. Evidently innovative in its execution, Aftersun is a wrenching memoiristic drama that is both emotionally piercing and stylistically daring, risky in its venture and dexterous in its adventurousness.

Measured and deliberate, the film avoids grandstanding – the narrative’s strengths are subtle, speaking volumes through intricately mapping Sophie’s labyrinth childhood memories. Nothing much happens in Aftersun. There is an ordinariness that follows the father-daughter pair and an extraordinary form of devoted kinship that shimmers in the quietude. Told from Sophie’s eyes, the film doesn’t give answers but rather, leaves us to search for them.

Heartwrenchingly tender and melancholic, the movie hits hardest after the credits roll when the reasoning behind the entire plot finally dawns upon viewers, effortlessly deconstructing themes of loss and grief without excessively harping on tear-jerking tropes. With every scene hitting a chord in me, the film capitalises on the universal and primal conditions of familial attachment, belonging and care. Even as a few hours passed after the film, my subconscious mind was still in its own emotional overdrive.

In one of the movie’s most affecting scenes, Calum reminds Sophie, “I want you to know that you can talk to me about anything”. Refusing to disclose his own difficulties, such words paint a portrait of the reassurance from a father to a daughter that feels as comforting as it is hypocritical. Wells is masterful in the way she manoeuvres through time, relying on an intuitive narrative register following strings of emotion rather than the rigid mechanics of the plot. Dovetailing past and present, reality and imagination, Aftersun’s remarkable ability to transcend spatio-temporal confines points to Wells’ directorial prowess in navigating Calum’s lyrical loneliness and Sophie’s growing pains. The boundaries between memory and reality become blurred to the point of coalescing into one haphazard entity.

In the central performances starring the charmingly reticent Paul Mescal and screen newcomer Frankie Corio, Calum and Sophie carry such a compatible chemistry that their dynamic feels akin to non-acting with dialogues resembling the smooth and calming flow of Calum’s Tai Chi repertoires. The intensity of their bond is vicariously infectious – the audience inevitably develops a profound emotional attachment that leaves one’s psyche reeling once the film ends. You are suddenly hauled out of their world and all that is left is a gulf of emptiness.

Paul Mescal, a household name after his breakout role in Normal People, has something about his face that is both charming and heartbreaking. Possessing a persona that is vulnerable yet somewhat distant, he comes across as elusive with an enigmatic past, offering little explanation around his disposition and drawing great intrigue towards his backstory.

While the mainstream audience might be familiar with Mescal, fresh-face Frankie Corio proves to be a refreshing twist. Without knowledge of her inexperience, it is almost impossible to be able to decipher the novice actress’s proficiency, having borne a finesse that is far from amateurish.

Initially only an independent film, Aftersun is a small pearl of contemporary coming-of-age cinema in what can sometimes be a sea of hackneyed chick flicks. Some films we forget after a few hours, but this film was one etched deep within my mind like an anchor, posing as a reminder to reflect upon my own relationship that I hold dear and near. A movie that broke my heart in the worst and best way possible, it sheds light on how love and grief live side by side with each other.

——————————————————————————-

This review is published as an extension of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme organised by The Filmic Eye with support from the Singapore Film Society.

About the Author: Jia Hui has a love-hate relationship with potatoes but thankfully, this is not the case for films. When not daydreaming about films, she can be found dreaming about her other loves, food & design. And yes, all while taking her gap year.

——————————————————————————-