Film Review #160: ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT

All We Imagine as Light Review

(Some spoilers included!)

Illuminating the vulnerable intimacy of yearning in a society that shames.

All We Imagine As Light (2024) by Payal Kapadia has burst onto the international film industry in a largely unprecedented manner, highlighting not just the Indian filmmaker’s own filmography but also actualising the path of exposure for South-Asian films and talents on a global scale.

It has made history in a magnitude of ways; it is the first Indian film to win the Grand Prix at Cannes and the first to be nominated for a Palm D’Or in over three decades. It has also attained two Golden Globe nominations and its success seems only to be building momentum as we await on the precipice of the film's eventual legacy. I mention the awards run not to equate the measure of the film’s success to the amount of accolades it accumulates but rather to highlight its poignant role in history. This movie has earned international recognition for the Indian independent cinema industry, a sector of south-asian filmmaking that is historically underrated and far overshadowed by the more celebrated and prestigious Bollywood.

All We Imagine As Light

is a work of art. The beautifully gripping movie follows the lives of two women working as nurses in the bustle of Mumbai, one of the world's most populated cities. Prabha, a married woman who has lost touch with her immigrant husband away in Germany, shares a room with Anu, a young and vibrant personality engaged in a passionate relationship with a man who comes from a different religious background, a fact that results in their relationship being highly contentious in the conservative social climate of the city. When Prabha’s friend Parvathy, the elderly cook at the hospital, is forced out of her residence in Mumbai and has to relocate to her hometown of Ratnagiri, Prabha and Anu follow along to the seemingly unassuming sleepy village to help Parvathy move.

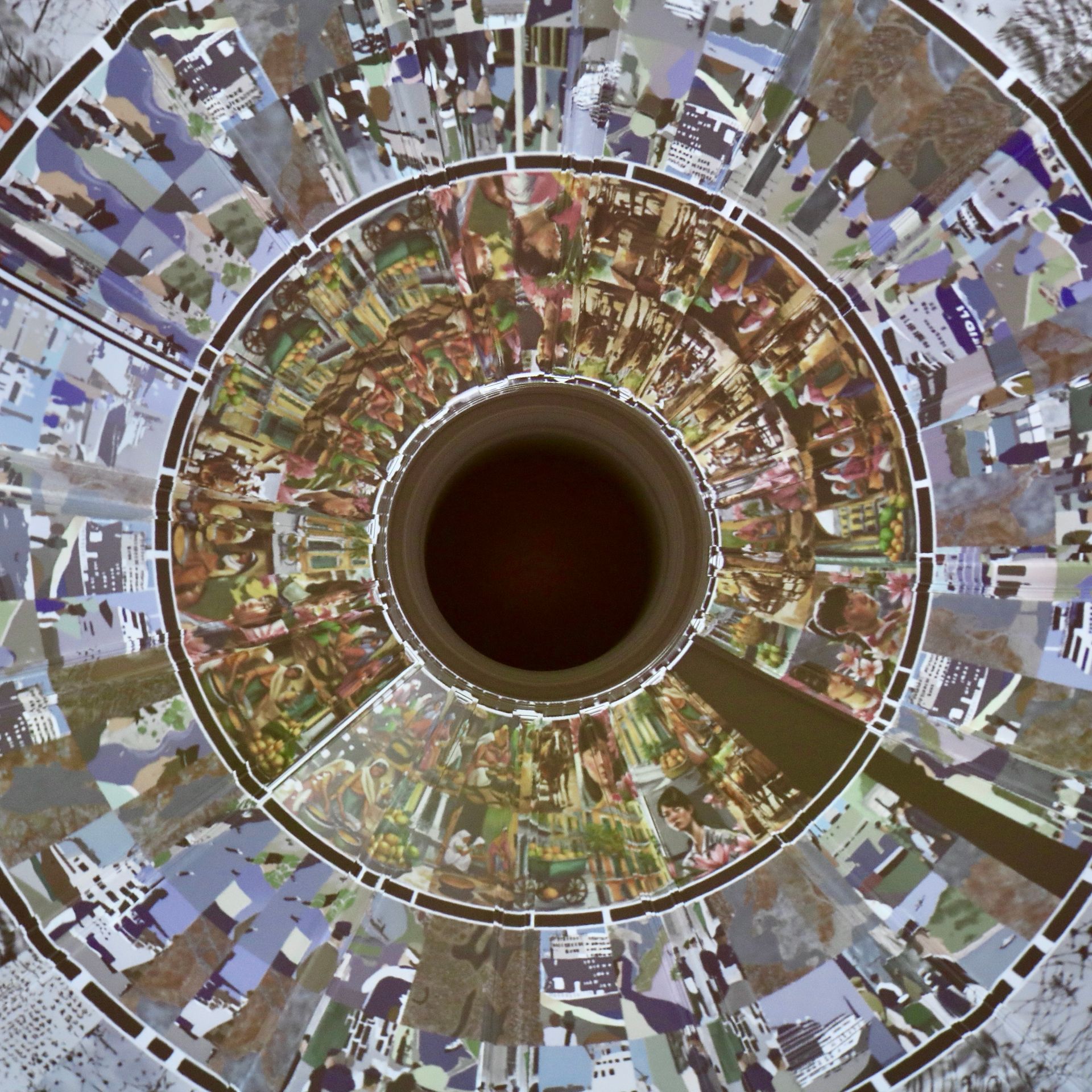

The film explores the deep need for intimacy that the women harbour, with one having to stifle her yearning while another celebrates it, albeit in secrecy and with a shadow of unease. The backdrop of the film, the relentless concrete jungle of Mumbai, perfectly juxtaposes the deeply human aspects of Anu, Prabha, and Parvathy. The city is hard, relentless and crudely pragmatic, running on millions of occupants daily, thereby inadvertently emphasising the women’s insignificance in the larger picture. However, it is the strength of the women’s friendships and their near familial dependence on each other that negates the apparent frivolity of their lives. This is heightened when the women travel to the slow and serene Ratnagiri and eventually make strides in addressing the reality of their fallacies.

Kani Kusruti plays Prabha with an astonishing level of depth and nuance, reflecting the deep-seated aching simmering underneath a layer of gentle stoicism. Just in the way Prabha sits alone in the silent introspective moments of the movie, we are hinted towards the world of pain that she has lived through and suppressed before we come to meet her as a character in the film. The first glimpse we get of her raw need for intimacy is when she receives an unexpected gift from her husband, a rice cooker from Germany. As she curls around that rice cooker, the first point of connection she has received from her partner in a long time, Prabha recognises her own vulnerability as she embraces the cold metallic machine, grasping at any remnant hints of warmth or affection she can detect. Any traces of a husband so far gone, he is a whisper of a memory.

This paralysingly raw depiction of wanting is juxtaposed with the vibrant and forceful passion that Anu engages in with her boyfriend Shiaz as they travel around Mumbai looking for privacy to practice intimacy in any convenient corner of the city. Their youthful joy and the thrill of young romance are threatened by the very age-old question that has haunted the youth of India for generations, ‘What will people say?’ Anu and Shiaz’s interreligious relationship hidden from their communities creates a looming threat that hangs over their heads, sullying their tender moments and fondness for each other.

As an avid fan of romance and how it is depicted in films and books, I would like to highlight probably the best scene of physical intimacy ever shown in a South-Asian film. As Anu and Shiaz take the next step in their relationship and become physically intimate, we get wholly beautiful and mesmerising scenes of them as they take this path together. Filmmaker Payal Kapadia and her cinematographer Ranabir Das create this portrayal of intimacy that highlights the deep reverence and trust that Anu and Shiaz have in each other. There is a clear emphasis on the scenes being portrayed through a strong female gaze. The camera approaches Anu and Shiaz in the throes of passion with respect and affection, mirroring the very crux that is the premise of their whole relationship, that their wanting and need for affection is true and surpasses superficially constructed social boundaries. It is heartening to see such a rich, respectful and unrestricted account of physical intimacy in a South-Asian film, and one that is especially driven by the female narrative.

Mumbai itself becomes a character in the film. The city that rewinds at night, brutal in its efficient and persistent forward march, has no regard for who it has to step over to get ahead. There are no soft spaces for vulnerability in the harsh artificial lights of the city so it falls on the characters to carve it out for themselves, which we see through the gorgeous representation of female friendships in the film.

On the other hand, moments of emotional connection between men and women are tethering on the edge of taboo, something to be highly conscious of lest it result in a shamed encounter or social ostracisation. Payal Kapadia has brought us into the lives of these women, we feel constricted and trapped as they do and we breathe in the lush, luxurious rich air of the ocean breeze as the characters open themselves up to us at the end, allowing us in on the intimate moments between friends and lovers.

If it isn’t obvious by now, I am a huge fan of this movie, of Payal Kapadia, and of the underrated South-Asian indie cinema industry. I eagerly await her upcoming films and can promise that I’ll be there, sitting front row, ready to see and be seen by her filmography.

---------------------

About the author: Perpetually curious about film, art, and thought.

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.