Film Review #130: JURASSIC PARK

“If

The Pirates of the Caribbean breaks down, the pirates don’t eat the tourists”: Revisiting

Jurassic Park

(1993)

Dear reader, this essay is a pretty deep dive into Jurassic Park (beware of spoilers) rather than a conventional review. It’s recommended that you watch the film before reading this essay in order to get the most out of it.

1. Returning to

Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park (1993) was among the first few live-action films I ever saw in the cinema as a child. I watched it twice in the cinema and multiple times on VHS. But I don’t think I ever made a conscious effort to revisit it when I started to develop a more serious interest in film from around the time of my A-Level studies. Of course, over the years, I never ceased to say positive things about

Jurassic Park in casual conversation, usually something to the effect of “The dinosaurs still look real even after all these years.” Now, this wasn’t because I was confident that the special effects had aged well. Rather, it was simply because this was something that the people around me always seemed to agree with quite reflexively. I never felt any discomfort about reusing this little white lie because, at some level, I had always believed that

Jurassic Park would hold up under contemporary scrutiny, though perhaps not for reasons to do with its special effects.

To put my own theory to the test, I re-watched

Jurassic Park recently from the start to the end for the first time in a very long time. Truth be told, I lost a bit of confidence in my earlier assumptions before putting the film on. I wondered briefly if my memories had been clouded by nostalgia. Regardless, I ended up thoroughly enjoying my re-introduction to the world of

Jurassic Park.

2. Shooting a Dinosaur

I wasn’t wrong about the special effects. Some of them have aged visibly. But this doesn’t diminish the impact of the dinosaur scenes and set pieces. The dinosaurs are still presented with a certain sense of scale, solidity, and spectacle that more recent films armed with the advantages of modern special effects have not been able to replicate. How was this achieved? Much has been said about the film’s judicious mix of CGI and animatronics. Also, as with

Jaws (1975), the storytelling in

Jurassic Park adheres to the principle of “less is more”, which amplifies the potency of each successive unveiling of the park’s dinosaurs. Even as a child, I was somewhat aware of these factors. I can still remember the grown-ups around me marvelling at how entertaining the film was even though the dinosaurs had very little screen time.

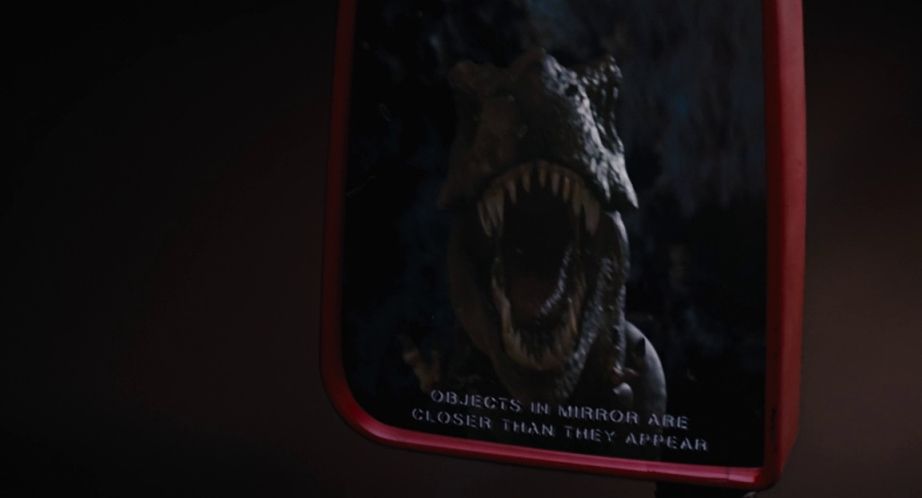

Now, re-watching the film as an adult, a whole host of other things stands out for me. I’m more conscious now of how the “felt” physicality of the dinosaurs, as opposed to the weightlessness or floatiness of many modern CGI creatures, is as much the result of shooting and storytelling decisions as that of the use of practical effects. The dinosaurs are almost always framed tightly. It doesn’t matter which species we’re looking at or what the dinosaur is doing. It also doesn’t matter which part of the dinosaur we’re looking at: the entire body, a part of the torso, a claw, a foot, or the head – when it appears, the dinosaur or body part thereof fills a large part of the frame. There is also usually a human point of reference sharing the frame with the dinosaur. This could be a human character or a man-made object, one of the park’s vehicles, for example. If there’s a human character in the scene, we will get, as one other reviewer has pointed out, a good number of well-acted reaction shots, either one of wonder or terror. Scale, power, and physicality are thus communicated – and a sense of awe, intimacy, or spectacle is correspondingly induced – in the most direct of ways. One interesting example would be the famous shot of the reflection of the T-Rex’s roaring visage in the side mirror of the park jeep as it catches up with it in a chase scene. It’s only a reflection, but the T-Rex’s gaping jaws fill a large part of the frame. We also notice, at the bottom of the side mirror, the following warning in block letters: “OBJECTS IN MIRROR ARE CLOSER THAN THEY APPEAR”.

3. Relatable Terror (or Wonder)

The audience is also reminded of what the dinosaurs are capable of even when they’re not on the screen or are obscured. “Less is more,” so the saying goes. But “less is more” can also be downright boring if mishandled or taken too literally. It will work, though, if it provides time and space for the creature’s physicality and potential to register in a proper build-up. And it works particularly well in

Jurassic Park because such time and space are filled with relatable references to things that we can reasonably expect the audience to understand or to have even seen or experienced before. The use of rippling water (in a cup or otherwise) to announce the imminent arrival of the T-Rex has long since become a cinematic cliché. But it’s a perfect example of what I’m getting at. It is recognizably how a large animal could announce itself. The opening scene where a Velociraptor triggers a deadly workplace accident is another one. We can only see bits of the raptor through the slats of the transport container. But it’s the opening shots of the waiting park staff – armed, eyes fixed on the imminent delivery of the raptor, and led by a specialist, the game warden Robert Muldoon (Bob Peck) – that tells us what we need to know about the dreaded thing in the large box. What are the real-world threats or familiar cinematic ones that need to be mechanically restrained or shadowed by an armed welcome party? Who or what moves from place to place in a large sealed box? Serial killers? Hannibal Lecter? Destructive weapons? A dormant vampire? Consider, too, the raptor feeding scene. We see the raptors’ meal – a live cow – lowered into the raptor pen; we see the plants in the pen shaking, almost like rough waves; we hear the raptors tear the cow apart; and we see the mangled harness emerging from the pen once the feeding is done. This is essentially a large-scale version of a piranha feeding frenzy.

Jurassic Park seems to set its raptors up as a tiny band of intelligent human-like serial killers or hunters who eventually escape from “prison”. And I do mean tiny. As a child, the fact that there were only three adult raptors in the park completely flew over my head. I became aware of this for the first time only upon re-watching the film with the explicit intention of writing about it. Why only three? We learn from Muldoon that one raptor – the “big one” – “took over the pride and killed all but two of the others.” “That one,” Muldoon warns, “when she looks at you, you can see she’s working things out.” The raptors, he further notes, have been probing the electric fences for weak spots. We learn how human-like and clever the raptors are long before we even see them ambush Muldoon and open the kitchen door. Would a horde of raptors have been as cinematically effective as only three of them? I doubt it. If the raptors are already everywhere, the audience won’t get the chance to torture themselves by imagining where they may pop up next. It’s not for nothing that slasher films usually feature solo killers. The alien in Predator (1987) – another non-human but human-inspired hunter (or serial killer) – also prowls the jungle environment alone.

I can also now see how the main action set pieces – namely, the T-Rex paddock scenes and the raptor scenes – derive a lot of their effectiveness from their claustrophobic aspects. There is nothing intrinsically terrifying about a large carnivorous animal. But being trapped with one in close quarters certainly is. Granted, the T-Rex paddock scenes take place in an open-air setting. However, most of them are orchestrated around and

within the park’s tour vehicles. We see the T-Rex knock over the tour vehicle containing Lex Murphy (Ariana Richards) and Tim Murphy (Joseph Mazzello), shattering the car’s glass canopy. It presses its weight on the overturned car as it attacks it, threatening to crush the children or to drown them in the muddy ground. In this entire set piece, the overturned tour vehicle is as much a threat to the human characters as the T-Rex is, even when they’re no longer trapped in it. The T-Rex disappears from the final act of this set piece, which revolves entirely around Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and the Murphy siblings evading the falling tour vehicle as they climb down the paddock’s side walls and later one of the large trees within it. The T-Rex paddock scenes work because the tour vehicle plays the role of a secondary (and, later, primary) threat. At some level, we can only feel meaningfully threatened by things that we know or find familiar and, well, none of us has seen a T-Rex in the flesh before. But we can easily relate to the claustrophobic terror of being crushed inside a cramped hulk of twisted metal and broken glass or of frantically climbing down a tree while a heavy object crashes through the branches above us.

We see similar principles at work in the raptor scenes. Like the T-Rex, there is nothing intrinsically terrifying about a raptor (or a known human killer, for that matter). But being trapped with two of them in a kitchen with few obvious hiding spots and with clanging metal surfaces and utensils that threaten to give your position away certainly is. So is having a snarling raptor head pop up through the panels below you while you’re crawling through an air duct. So is being chased by one in the restrictive walkways of an underground power shed. The raptor scenes recall those from slasher films (analogues for escaped serial killers deserve no less). Like many of the raptor scenes, slasher films involve people being stalked and killed by implacable and seemingly

all-knowing masked humans (or non-humans even), sometimes in tight spaces. A good number of the shots of the raptors are shots of their “weapons” rather than full body shots: their jaws and teeth, their powerful legs, and, of course, their claws. Perhaps more interestingly, a number of the shots of the raptors are

reaction shots, underlining their intelligence and their alertness (they always sneer knowingly). The raptor scenes work because they are, at some level, familiar and relatable in an unsettling way. No one on this planet has ever been hunted by a raptor in tight spaces before, but a good number of us can easily imagine the terror of being attacked by a fellow human being in a place with few avenues for escape. As an aside, wasn’t the shark in

Jaws set up as an underwater serial killer?

The raptor scenes are familiar in another way. There is a piece of concept art in Jurassic Park: The Official Script Book that places the raptors in a haunted mansion-esque environment. It never made it into the film, but some of the raptor scenes nonetheless still possess a haunted mansion quality. In both the film and in your standard haunted mansion fair ride, ghoulish heads and grasping limbs (or severed ones) pop out of unexpected places in dark and spatially restricted settings. The kitchen scene with Tim and Lex certainly possesses this charm. The Murphy siblings may as well have been crawling around their own house in order to evade the bogeyman who has just trundled out of their bedroom closet.

The dinosaur scenes in

Jurassic Park

still work well because of their relatable or familiar qualities. This, of course, also applies to the scenes where no one is getting killed and eaten. Consider the scene where the main characters observe the hatching of the raptor egg in the park lab. We see, in intimate medium close-ups, the main characters hunched and whispering around the incubator, like children coaxing a shy puppy out of its cage. Consider, too, the veterinary and petting zoo undercurrents of the Triceratops and Brachiosaurus feeding scenes respectively. These scenes are impactful because they trigger heartfelt callbacks to the real world.

4. Humans of Jurassic Park

Now, what of the human characters? It’s often said that the characters in Jurassic Park are thinly sketched. I don’t necessarily disagree. But several of the main characters – namely Grant, John Hammond (played by the late Richard Attenborough), and Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) – are sufficiently

textured, in no small part due to the skills of the actors playing them, as to be worthy of being taken seriously by the audience. Spielberg and his actors succeed in making it seem as if these characters are

inhabiting the world of

Jurassic Park as opposed to merely appearing in it. In the helicopter ride to Isla Nublar, Hammond describes Malcolm as a “rock star”. Goldblum’s performance (not to mention Spielberg’s direction) in this film is such that we can believe that, even when “off-screen”, Ian Malcolm is indeed a rock star mathematician and has been for some time in the world of

Jurassic Park. Grant’s introduction is another case in point. It’s just another day at the dig site with Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) and the volunteers. But it shows us so economically

who Alan Grant

is in

this world, even before we hear Hammond describe him and Sattler as “top minds” in their field. By the time Grant is done teasing the kid who didn’t think that raptors were scary (“More like a six-foot turkey”), we can believe that he’s a world expert on dinosaurs and that he’s therefore the right person to endorse the park and reassure its investors.

We can also identify with the characters in Jurassic Park because, like Chief Brody (played by the late Roy Scheider) from Jaws or Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss) from Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), they are regular people – played by good actors, it bears repeating – plunged into extraordinary and other-worldly circumstances. It’s easy to root for a small town police chief or an electrical lineman who’s out of his depth. In the same way, it’s easy to root for the characters in Jurassic Park because they are patently not monster-dodging action movie characters. That sort only appears in the recent Jurassic World series (2015-2022). All we get in the first one are regular academics and kids. Even John Hammond is “normal”. He’s a CEO, but of the avuncular Walt Disney variety. He’s not the type of CEO who’s going to take to the skies in a helicopter to hunt down rogue dinosaurs, as the late Irrfan Khan’s Simon Masrani does in Jurassic World (2015). Hammond shows his complacency in several scenes, but he doesn’t say or do anything on-screen that comes across as larger-than-life. When the power fails to come back on, he obligingly, and rather innocently, reassures a nervous Sattler with the following: “All major theme parks have delays. When they opened Disneyland in 1956, nothing worked.” “Yeah, but, John,” Malcolm, lying injured on a table, reminds him, “if The Pirates of the Caribbean breaks down, the pirates don’t eat the tourists.”

We can root for and relate to the characters in Jurassic Park because, like Chief Brody from Jaws, most of them try to do the right thing even when they’re out of their depth. Only the lawyer runs. But his real crime, the audience sees, is abandoning the children. “He left us. He left us,” Lex mutters, as Donald Gennaro (Martin Ferrero) scurries off in the rain for the illusory safety of the park bathroom. It is Grant (and Malcolm, albeit less assuredly) who steps up in spite of his earlier coolness to the kids. Once Grant and Lex are finally safe at the bottom of the side walls of the T-Rex paddock, he tells her to stay put while he goes after her brother, who’s stuck in the tour vehicle that’s fallen into the top of a tree. “He left us. He Left us,” Lex continues to mutter. “But that’s not what I’m going to do,” Grant tells her. When Grant reaches Tim, they exchange words that many a parent at the playground or at the end of a misjudged theme park ride would find familiar. Tim tells Grant that he’s thrown up. “Tim,” Grant says, “I won’t tell anyone you threw up, just … just give me your hand.”

A large number of the scenes in Jurassic Park take place in the park’s indoor facilities, particularly the control room and the bunker. While I was re-watching the film, I was struck by how watchable the “on-site” workplace scenes were. Take the control room scenes, for example. The control room is lightly staffed. We see uniformed staff walking here and there in the background, but it looks as if the whole park is managed by Dennis Nedry (Wayne Knight) and Ray Arnold (Samuel L. Jackson). We soon learn – courtesy of a minor rant from Nedry – that the park’s operations are highly automated. Later, we’re informed, via a throwaway line, of the departure of park staff for the mainland at around the time of the approaching storm. Keeping the control room lean allows for a tighter focus on the characters in the room. Nedry, Arnold, and Hammond genuinely sound like colleagues who have been working together (and, in the case of Nedry and Hammond, getting on each other’s nerves) for some time. “I will not get drawn into another financial debate with you, Dennis. I really will not!” Hammond says, when Nedry alludes to his being underpaid for automating the park’s operations. “There’d be hardly any debate at all,” Nedry retorts. The control room scenes, quite naturally, are filled with IT and workplace admin-laden lines. But Wayne Knight and Samuel L. Jackson make these lines sound believable. Knight, in particular, succeeds brilliantly at sounding just like the sort of guy who would leave junk food wrappers strewn all over his workstation – we know the workplace personality type. When the fences start to fail after Nedry sabotages the park, Hammond barks, “Find Nedry! Check the vending machines!”

Stripping the park of most of its (skilled) personnel creates space for small and relatable moments. A friend of mine recently suggested that I should take a closer look at the scene where Hammond wistfully explains his motivation for building the park to Sattler in the visitor centre restaurant. They’re alone and the power (and hence the refrigeration) is already out. Hammond is eating ice cream. We see several tubs on the table. “They were all melting,” he says, when Sattler comes over to join him. Later, in the bunker, Hammond fumbles more than once, as grandpa would in a home power outage. As Sattler prepares to head out to the power shed, Hammond notes that he should be the one to go instead, because “Well, I’m a … and you’re, um a …” Sattler heads out anyway. “Look … we can discuss sexism in survival situations when I get back,” she says. When Malcolm tries to offer Hammond a small bit of advice on how to guide Sattler through the power shed, Hammond snaps back, “I understand how to read a schematic.” Sattler reaches a dead end, and Malcolm snatches the walkie talkie from Hammond.

5. “We have all the problems of a major theme park and a major zoo and the computer’s not even on its feet yet.” - Ray Arnold

Jurassic Park still holds up because a large number of its scenes are relatable in some way. Now, this isn’t the same thing as saying that it’s a realistic film. But, while re-watching

Jurassic Park, I couldn’t help but think of one of the late Roger Ebert’s observations about Batman Begins (2005). “The movie,” Ebert wrote, “is not realistic, because how could it be, but it acts as if it is.”

Jurassic Park, at least for me, successfully pretends to be realistic by daring to be about the

park rather than just being about the cloned dinosaurs. There are dinosaurs in the film, yes. But the film dares to spend most of its runtime lingering around the physical infrastructure of the park: its well-designed vehicles, its tall electric fences, the automated vehicle tour (narrated by the late Richard Kiley, who was playing himself), the control room (with its two main administrators), the bunker, the power shed, the T-Rex paddock, the raptor pen, and other places. More importantly, the film doesn’t overplay the park’s sophistication. To put it another way, we’re not shown so much that we lose the ability to feel that this is just a big zoo, only its animal exhibits happen to be dinosaurs.

Jurassic Park succeeds in pretending to be realistic also because of its characters, none of whom are written or played as larger-than-life. This is a film that is carried by its actors. The lunch scene (Chilean sea bass is served), where the film’s themes of technological hubris are spelt out explicitly for us in a minor info-dump, is a case in point. “Genetic power is the most awesome force the planet’s ever seen, but you wield it like a kid that’s found his dad’s gun,” Malcolm warns. The lines in this scene have aged remarkably well. In another part of his mini-lecture, Malcolm tells Hammond that his “scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” He may as well have been talking about AI. In the hands of a different set of actors, such lines could easily come across as too direct. It is to the actors’ credit that this scene, which is intent on telling rather than showing, doesn’t feel forced or boring. This really feels like how a polite meeting between cautious academics and a less cautious technology entrepreneur (“how can we stand in the light of discovery, and not act?”) would go. The lunch scene’s effectiveness is also partly due to the ambience of the private dining room. Or are they having lunch in a conference room? I can’t really tell. Whatever the case, the room has a bit of the feel of a small dark auditorium. There’s an automated slideshow clicking away, flashing park promotional material on the walls. We see a few lights on the walls. They provide a deliberate dose of delicate backlighting for the characters as they speak, making them look like expert guests on a nightly news show and underlining the gravitas of their words. Even what is effectively a lunchtime seminar is watchable. It’s a small but telling indicator of why Jurassic Park still holds up, even after all these years.

---------------------------

About the author: Benjamin Choo is a Senior Lecturer at the Singapore University of Social Sciences. As you can probably tell, Goodfellas is one of his favourite films. But he has many others and he's hoping to share his thoughts on them with you in future pieces for the Singapore Film Society. Stay tuned for more contributions from Benjamin.