(JFF 2023) Existential Booksellers and Filmmakers in 'Polan' and 'Your Lovely Smile'

[JFF 2023]

Existential Booksellers and Filmmakers in Polan and Your Lovely Smile

*This essay may contain plot spoilers. Reader discretion is advised.*

A few years ago I watched from a monitor as an actor recited, “If I had such a hard time quitting music, don’t you think I’m meant to do it?” The short film was never released, but the line comes back to me in the moments where grief over failure and the fear that this finally, is the moment my time in film ends strikes. As I saw myself through these moods, it became clear to me that it was never a question of extracting myself from film: it was to lose myself in the work of it and make it sustainable.

At this year’s Japanese Film Festival, I found the courage to stick with that imperative in the company of the booksellers of

Polan

(2022) and the filmmakers in

Your Lovely Smile

(2022). The central concern of the films’ subjects is not the crossroads of pursuing money or passion. Instead, having already made the decision to pursue their chosen careers, we find them in medias res. The result is not so much a celebration and valorisation of cultural workers as it is an insistent affirmation of the right to walk the path one desires. It isn’t that there’s an absence of self-doubt, frustration and helplessness; nor is it that there aren’t impossible obstacles to reckon with, which span stingy landlords to an indifferent audience. It’s the fact that they are met with a steadiness and stoicism that belies the existentialism of these booksellers and filmmakers who are all too busy with making things work to lament their misfortune.

Described as “chalan-polan” (Japanese: happy-go-lucky) in his youth, Polan’s namesake Kyosuke Ishida, was a committed student protestor in his youth. He held fast to the ideal of running a vintage bookstore while other protestors began to wear suits and apply for office jobs. Now he sports a newsboy cap and dark, stiff fabrics, throughout the length of the documentary — a most practical uniform for extended contact with dusty old books in crates and shelves that must constantly be stocked to optimise a customer’s browsing experience. Workwear fit for a life spent amongst books.

Polan in the daytime.

At Polan, the only indication of the store’s closure is an unassuming piece of paper stuck to a bookshelf. Otherwise, it’s business as usual. Why waste time on a grand announcement when they were going to continue what they were doing anyway? Along with Polan’s staff, Mr Ishida and his wife, Chiseko Ishida, flurry through the bookstore tending to customers, sorting and pricing books, restocking and aligning their shelves between cashiering duties and completing online orders that, despite everything, has maintained steady sales and allows them to find a way to persists in negotiating the cooperation of desire and the practical. In an age of industrial nostalgia and romanticism for the purity of analogue experiences, the elderly couple’s migration to bookselling online is only an evolution of their bookselling career. They are booksellers through and through, concerned only with getting books into the hands of their customers by any means necessary.

Of course it would’ve been great if they had retained their store. Mr Ishida iterates they would have continued operating the store “by any means necessary” — if it weren’t for the disruption of the pandemic and more crucially, an unsympathetic landlord with multiple properties who refused to make a small reduction in rent to avoid setting a precedent for other tenants. And so Mr Ishida packed up the shop with his wife, leaving the secluded corner of Tokyo abandoned, barren and dim. In a closing note, director Nakamura Kota informs the audience that no one has taken up Polan’s former space. Meanwhile, the Ishidas continue selling books online and at book fairs while their staff, past and present, opened their own book nooks across Japan. Save the empty rental unit, everyone’s lives went on.

Rental space after Polan’s closure.

If Polan depicts the duality of endings and beginnings,

Your Lovely Smile is a wry meditation on how making progress is often more static and repetitive than it is marked by dramatic evolution. Hirobumi Watanabe, maverick director of Japanese independent cinema, stars in Lim Kah Wai’s metatextual narrative about independent cinemas and a critically acclaimed filmmaker trying to sustain himself beyond the festival circuit. With the axiom that filmmaking is life, Watanabe’s devotion to cinema takes on a comedic existentialism as he cannot seem to stop himself from making films even when his films aren’t in production. But it's not compelling enough to draw a devoted, paying audience; less so when it comes to independent films in an ongoing pandemic. To mitigate this doubled alienation, Watanabe’s persona treks across Japan to distribute his films to local cinemas. Much has been made of the reticence of the audience to venture beyond franchise and superhero blockbusters. I propose that in

Your Lovely Smile, that tendency to blame the audience is interrupted and the onus is on the filmmakers themselves to find an audience of their own.

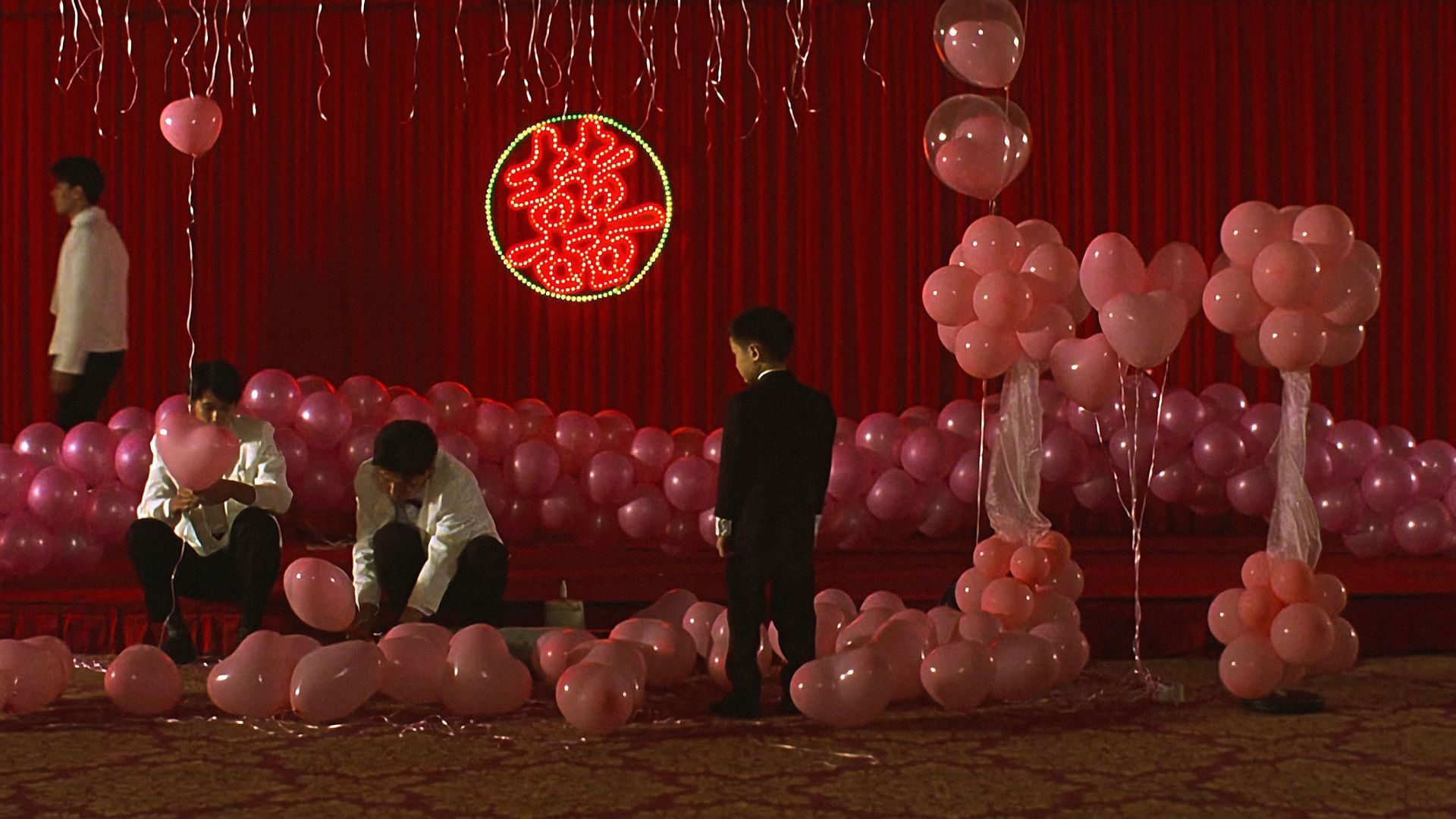

Watanabe-persona is confronted with an empty theatre.

Following the success of his last screening in Tokyo, Watanabe-persona sports a t-shirt with “Genius” emblazoned across the chest, holding on to the hope that entertainment giants like Japanese Big Four studio Toei, Netflix and Amazon would come calling and thereby deliver his genius to a mainstream audience. He is finally called into a meeting at a luxury resort in Okinawa, only to be met by a self-serving Big Four producer played by Shogen, who instructs him to complete a script based on the producer’s life and to cast the woman of the hour by his side. Watanabe-persona tries his best to complete it but as he has

admitted before, he doesn’t make films for an audience, especially not when the audience is a singular egotistical figure who delights in making himself the locus of power. The paradox of not making films for an audience yet being financially dependent on their attendance comes to a head: if he can’t bring the masses to his films, what he can do is screen his film in many spaces so that as many people get to see them as possible.

Watanabe-persona sets out on the road and soon finds it nearly impossible to convince any of the independent cinemas across the country to programme his films. Indeed, when he finally secures a screening, the struggle to generate publicity to attract an audience is endearingly comical until, despite some encouraging interactions, no one turns up. Facing a theatre full of empty seats, can a filmmaker still call himself a filmmaker if no one is there? Thank god for the camera that accompanies his trek to independent cinemas across Japan, rendering his life as film itself. Just as the endless nature of searching and waiting for an audience seems to tip into the Sisyphean, he winds up in a cinema at the end of the world — literally, as it faces permanent closure. Presented with an opportunity to meet a small but dedicated audience regularly but in the capacity of a cinema worker, Watanabe-persona takes it on. It’s what he was in search of all this time. Soon enough, he is an elderly man hobbling to the front to greet this audience of his own.

An elderly Watanabe-persona greeting the audience at the end of the movie.

——————————————————————————-

About the Author: Sasha seeks to reify the fugitive effects of looking through language. She received her BA in 2021 and has worked with HBO Asia, the Singapore International Film Festival and the National Archives of Singapore.

——————————————————————————-

Japanese Film Festival 2023 runs till 20 December this year. More info at https://jff.sg/