Commentary: Eric Khoo - Singapore’s First Auteur

Eric Khoo - Singapore’s First Auteur

As a final year student majoring in film directing, I have always been intrigued by the term “auteur”. A term that describes in essence, a film director who has a very distinct body of work, and is often credited to be the major creative force in a motion picture (Britannica, 2024). It is a term that has been thrown around a lot in film circles over the decades to describe legendary directors such as Akira Kurosawa, Stanley Kubrick, Francios Truffaut, and more recently, Christopher Nolan who is known for his big concept films and immersive IMAX sequences.

The term ‘auteur’ first originated from French film critics of the Cahiers du Cinema magazine of the 1950s, particularly Francois Truffaut in his essay "Une Certaine Tendance du Cinéma Français" ("A Certain Trend of French Cinema”) where he defined the auteur as a film director who has a distinct style and personality injected into his or her film.

I personally feel this distinct style and personality need not only be expressed through visual aesthetics (think Wes Anderson or Wong Kar Wai), but also thematic obsessions (think Denis Villeneuve or Yorgos Lanthimos). This led me into the rabbit hole trying to think — does Singapore have an auteur?

Eric Khoo certainly comes close, having directed over seven feature length films (including

Tatsumi, an animated film,

and the Cannes Palme d’Or nominated

My Magic)

and numerous short films. Suffice to say, Khoo has certainly built up for himself a substantial oeuvre for us to analyse. In this article, I would be focusing on three aspects that I feel can be considered in any assessment of Khoo as an auteur.

- His focus on social realism

Khoo’s first feature length film Mee Pok Man (1995) features bleak social drama infused with angst-filled melancholy. According to Raphael Millet (2015), it “single-handedly revived the Singapore film industry”. The story of Mee Pok Man revolves around the titular figure, a shy noodle-shop owner (Joe Ng) and a prostitute named Bunny (Michelle Goh). A chance accident brings both souls together but as Zhao Wei Films (2019) puts it “…just as the two lonely souls begin to connect, Fate intervenes and deals them a cruel hand.” The down-and-out protagonist, the bleak social realist tone and focus on heartland locations around Singapore would come to define Khoo’s body of work in time to come.

A still from Eric Khoo’s debut feature Mee Pok Man (1995) featuring Bunny and Mee-Pok Man

After a very successful festival run for Mee Pok Man, Khoo’s next feature 12 Storeys (1997) is almost an anthology of sorts, weaving together three stories of the occupants of a 12-storey HDB (public housing) flat. Again, Khoo focuses on the heartlands, choosing to tell a story that is part supernatural, part social realist which makes for a very interesting watch.

A still from 12 Storeys (1997) featuring a group of uncles featured in the film.

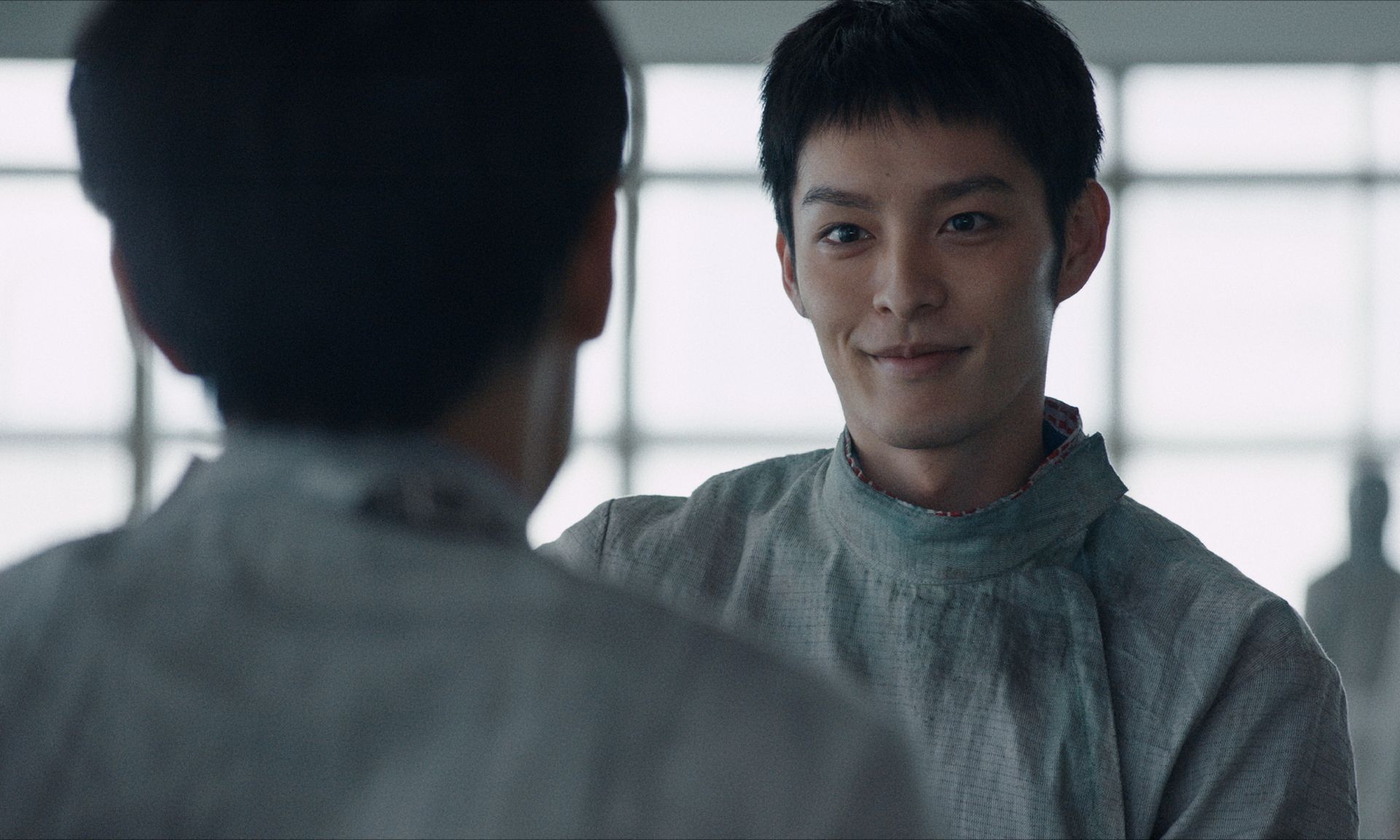

Even with his more recent films such as In the Room (2015), which features a pre-Parasite fame Choi Woo Shik, and Ramen Teh (2018), which features an international cast including Takumi Saitoh, Tsuyoshi Ihara and homegrown actors such as Mark Lee and Jeanette Aw, Khoo always focuses on the social realist aspect. For example, in In the Room, Khoo focuses on six short stories that span several decades — only connected by the same hotel room. The social realist aspect that Khoo famously employs comes in full force here, taking place in the form of the characters. From a rock and roll singer in the 60s to a married woman discussing her affair with her Singaporean boyfriend in the 80s, Khoo has this affinity for focusing on characters that you might see everyday and gives you the chance to be a fly on the wall, observing their most intimate and personal conversations.

One standout example I can highlight out of the six short stories in In The Room is First Time. The story focuses on a Korean couple discussing their romantic and sexual relationship in the room, bringing up problems and issues that pertains to their personhood. The conversation they have with each other feels very real and something that I do believe that people in real life would discuss. Therefore, I believe that one hallmark of Khoo’s work that he constantly revists is his focus on social-realist stories, regardless of his budget or cast.

2. His propensity towards the non-genre

Maybe this is a distinct trait of a true arthouse filmmaker, but something I noticed throughout his films is that Khoo leans towards not making genre pieces. Granted, the catch-all term for the genre that he works in is “drama”, he does not limit himself to genre conventions.

For example, My Magic (2008) could be said to be a classical narrative drama as it has, on the surface, a lot of ingredients that warrants one to think that way. However, if you were to dig deeper, you will find that there are a lot of discrepancies that lend one to think they are not really watching a “drama” piece. For instance, the “magical-realist” angle that is interwoven into the story. As the audience is primed to think that it is a social realist drama, they would not expect any “magical” things to be happening, however, in My Magic they do. Without giving away too much, this “magical-realist” aspect comes into play as the magical acts that Francis (the main character) and his son do not only is for entertaining their audience, it also is a viable way for them to get out of danger or situations which would not be deemed “realistic” in a more “realist” film.

Eric Khoo’s film My Magic (2008) which got him a Palme’dOr nomination at the Cannes Film Festival in 2008.

3. His heart in championing local cinema

When people think of an auteur they often (rightly so) think about the directorial works that a filmmaker has done. However, I would like to offer a fresh perspective on the auteur theory and include works that a filmmaker has produced.

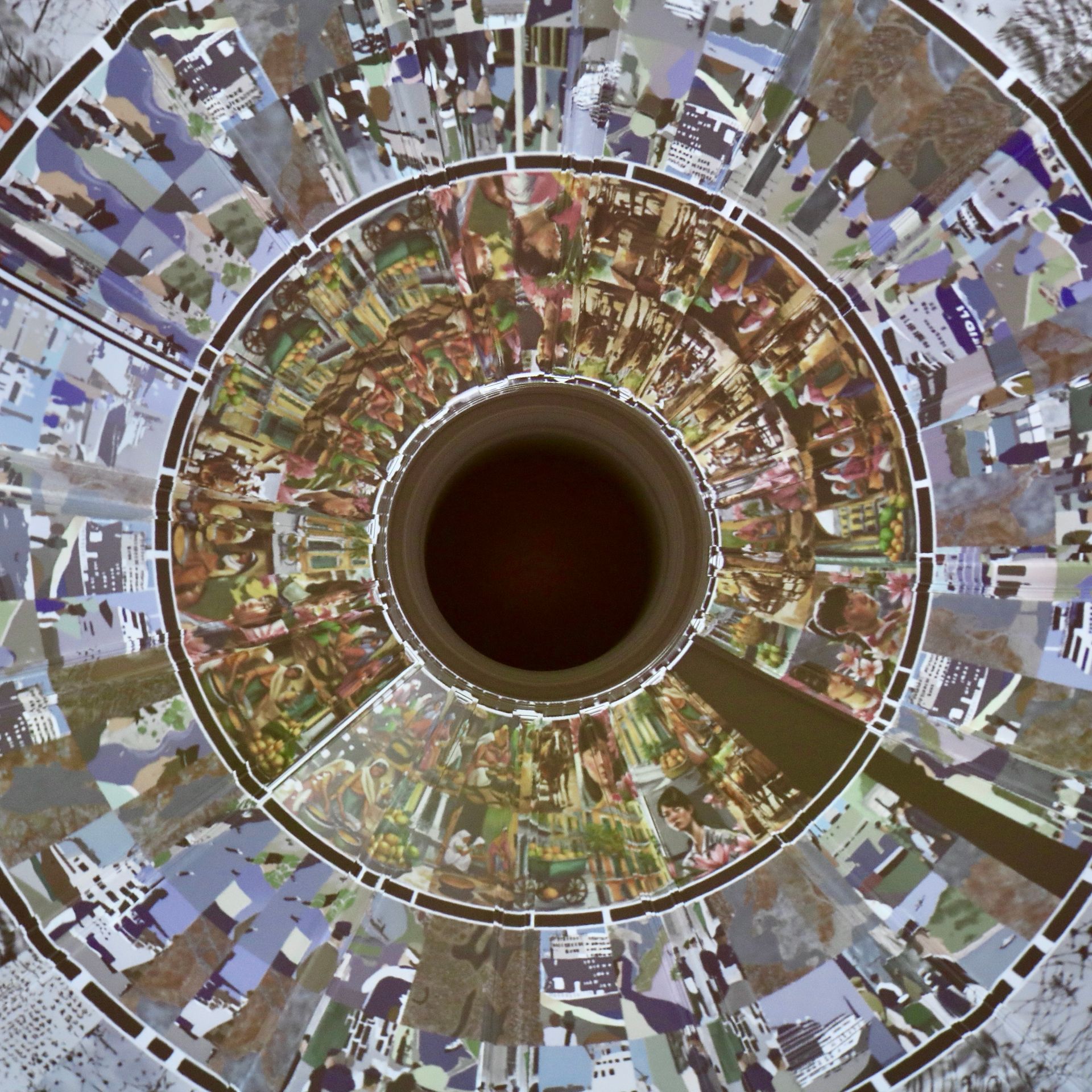

Creative producing is something that I feel is often overlooked when it comes to analysing a filmmaker’s body of work. Through Zhao Wei Films, Khoo’s production company, we can start to see a trend in the kinds of stories he champions.

From the slate of works that Zhao Wei produced, we can see that Khoo certainly loves to champion works of fiction that are created by young Singaporean filmmakers. Works such as Royston Tan’s 15 (2003) and 881 (2007), Boo Junfeng by way of Sandcastle (2010) and The Apprentice (2016), all of which were by emerging filmmakers who went on to become auteurs in their own right.

A still from Boo Junfeng’s Sandcastle (2010).

Therefore, I believe that Khoo really loves local cinema and wishes for it to flourish and he walks the talk by championing works and filmmakers who share the same sentiments.

In conclusion, the Singapore film scene should be grateful for its first auteur who has been making films since he was 30. I believe that without Khoo’s influence, we might not have had such filmmakers coming out from Singapore as Anthony Chen, Kristen Tan, Boo Junfeng and so many others telling such authentic Singaporean stories that matter.

——————————————————————————-

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.

About the Author: Arel loves people, including all the messy parts that come with it. He believes that everyone has a story to share and strives to share them meaningfully on the big screen. Other things Arel loves are his guitar, his blu-ray collection and his bed. You can catch more of him at bio.site/arelkoh.