Somewhere Beyond the Rainbow: From Southeast Asia to Hollywood

Somewhere Beyond the Rainbow:

From Southeast Asia to Hollywood—why black and white is the Golden Age

When one thinks of film, among the first things that come up might be colour. Film is a visual medium and colour is a striking element appreciated by hardcore cinephiles and casual audiences alike, cultivating the aesthetic of a cinematic landscape in its mise en scene, or visual composition. From the ever-beloved saturation of technicolour classic The Wizard of Oz (1939) to its modern counterpart Wicked (2024), colour in film has gone through many stages of evolution, yet its earliest form on the silver screen is largely overlooked and underappreciated. Black and white is a form of colour within its absence, and the black and white era made its place in the Golden Age of Cinema up until the late 1960s.

Above: The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Below: Wicked (2024)

The Golden Age was a period of innovation, marked by advancements in sound and colour techniques. However, black and white remained the medium of choice for everyday film production and films of cost-conscious producers like Roger Corman’s early work in the 1950s. Many things distinguish black and white film, apart from its timeless visual aesthetic. For one, the desaturation refocuses the viewer’s attention to other elements of the image, allowing the subject to be centric, and giving a frame depth or contrast in a way that elicits nostalgia or poignance. The medium and colour, or lack thereof, also allowed for greater technical freedom and creativity for filmmakers. As observed in a conversation with filmmaker Jonathan Miller (Alice In Wonderland), the very act of creating black and white film transmutes our colourised reality. With this canvas, filmmakers could reinterpret their surroundings and the world within their viewfinder.

Unfortunately, after the introduction of colour techniques and the advent of colour television as a day-to-day medium, producers’ and audiences’ demands shifted to colour production as the new standard, wiping out black-and-white cinematography. The people yearn for colour. In modern media, the same sentiment reigns; our fluorescent screens literally oversaturated with the constant stream of content. Typically, young people nowadays share the conviction that black and white films seem old, boring, or pretentious. Some relate the noir aesthetic to being arthouse, but contemporary black and white cinema seeks to prove they can be very accessible stories. However, with little demand for these films, the market continues to reject this format and distributors hesitate to purchase these films. Many of the few recent black and white films produced have remained unsold due to the presumption of limited appeal, like

Fremont

(2023) starring Jeremy Allen White; denied on the distribution front solely due to “the black and white problem”. This is an example of the unfounded prejudice towards colouring in cinema amongst the contemporary viewership market, but if more people gave it a try, they just might like it.

Call it old fashioned, but black and white films evoke technicolor emotion.

They made their mark as the Golden Age for good reason.

Hollywood’s rise to a cinematic powerhouse, earning itself the benchmark of the Golden Age of Hollywood, was jump-started by the Great Depression. The period saw a huge influx of films produced, bringing in a steady stream of creative narrative voices and directions. Some iconic ones, like

Casablanca (1942) by Michael Curtiz, Frank Capra’s

It’s A Wonderful Life (1946) and

12 Angry Men

(1957) by Sidney Lumet. During this period also emerged the pioneers that revolutionised modern cinema as we know it, from the “Master of Suspense” Alfred Hitchcock to Ernst Lubitsch who earned his namesake of the “Lubitsch Touch”.

Above: Casablanca (1942)

Below: The Shop Around The Corner (1942)

One of my personal favourites is Lubitsch’s The Shop Around The Corner (1942), which has held a spot on my Letterboxd top 4 favourites (@viciejade) list for a long time. The Shop Around The Corner, which later inspired the popular romcom You’ve Got Mail (1998), is a complex but sugar-filled enemies-to-lovers trope—two employees at a gift shop bicker endlessly but unknowingly fall in love with each other through the post as they send each other anonymous pen pal letters. The depth of the cinematography within that high contrast black and white mise en scene overlaid on the characteristic transatlantic accent and sophisticated manner of speech; the filmmaking adds a touch of gentleness to the romance. It’s a sweeping love, but it envelopes the emotions of those who witness it, something unique to the flair of the time.

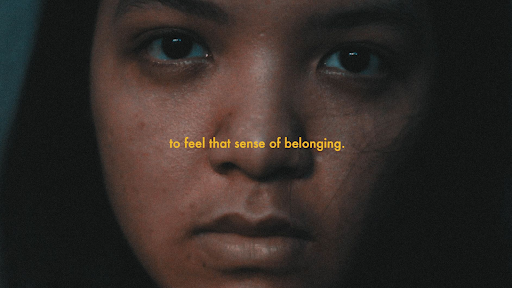

While the Golden Age of Hollywood is arguably underappreciated, inarguably overlooked is our own Golden Age, in Southeast Asia. The periods overlap, being from the late 1940s to the early 1970s in Singapore. While our country was budding, the

film scene was blossoming, reigned by two major film empires, Cathay Organisation and Shaw Brothers, producing hundreds of films largely in the Malay language. Singaporean/Southeast Asian cinema was pioneered most famously by silver screen legend P. Ramlee, who was an actor, filmmaker and musician. His body of work across genres includes films like

Penarak Becha (1955) where a common trishaw driver falls in love with a wealthy heiress,

Antara Dua Darjat (1960) where similarly a rich woman develops affections for a poor but talented pianist. His films tackle the prevalent class struggle, confronting the idiosyncrasies of Singaporean life as a common man, and offer both entertainment and biting commentary of the time that retains its value to this day.

Above: Penarak Becha (1955)

Below: Antara Dua Darjat (1960)

Somewhere beyond the rainbow of fluorescent screens is an oasis of black and white, a time capsule, a break from our times. On today’s screens, given the abundance of resources to make the most splendidly vibrant films, contemporary filmmakers sparsely reach for the less accessible and more expensive black and white film stock, save for a few gems like the heavily relevant Pleasantville (1988) and more recently Oppenheimer (2023). Monochromatic cinema has been widely overlooked on the cinematic colour spectrum, leading to a harrowing lack of preservation and only the odd restoration. Some such restorations are done in-house and screened at our very own Asian Film Archive, where there are regular screenings of restored films from Southeast Asia and beyond. If you’d like the rare chance to catch a P. Ramlee film on the big screen, Wisma Geylang Serai is also organising a series of screenings of some P. Ramlee classics from 10th to 27th March!

With more interest and support, more can be done to bring these films and this colour-genre back to life. There is little that is inaccessible if you seek it out—keep an eye out for black and white gems at local screenings, on your preferred streaming services or other sources like YouTube and Internet Archive, and add a little colour to your viewing horizon.

---------------------

About the author: Victoria Khine is a fresh graduate from Film and Literary Arts at School of the Arts, Singapore. She loves watching and making films, and she writes from the heart.

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.